Sine Hwang Jensen on Archiving Asian America

Sine Hwang Jensen is the Asian American and comparative ethnic studies librarian at UC Berkeley.

What about Asian American literature inspires you?

One of the things I find inspiring about Asian American archives and literature is witnessing the spirit of resistance and resilience. The big hearts of so many different communities and people. The complexity, creativity and depths of emotion and care. It's really incredible to carve a life amidst colonization; war; displacement; intergenerational trauma. There is all of this pain which tends to be the focus of disciplines like ethnic studies. But there is also the resistance, the joy, the everyday love, community love or family love. Those parts really inspire me and provide a balm for my heart in hard times.

I love what you said—making a life amidst all of this pain. How does pain manifest itself in the archives where you work at UC Berkeley, and what does making a life, or everyday love, look like in that context?

One example in the archives is the poetry written by Chinese detainees held on Angel Island in the early 20th century. The poems speak to suffering, but also resistance; anger; humor. By making a life, I mean the ways throughout time that we keep pushing ourselves and our communities forward despite huge barriers and huge opposition—the ways people cultivate hope and solidarity and love for each other in big and small ways. In the archives, you might find everyday correspondence like postcards and letters. It could be between friends, writers, or between a person and their mother, a person and their sibling. You might find community newspapers where people are analyzing or building solidarity and connection across huge geographical and experiential differences. You see all the ways in which these networks of relationships and support, which are often so invisible when we look at movement history or labor history, for example, really provide a network of care that sustains life. That's what I react to when I witness those tender moments between family, chosen or biological; it reminds me of the need for care, community and compassion that we often provide each other and ourselves despite so much hate, oppression, or invisibility. Even the care of witnessing each other’s pain with compassion is so huge sometimes. I often turn to poetry during times of crisis and lately, I’ve also been reading the work of Palestinian poets, for example. There is something about poetry that allows for deep witnessing that I appreciate.

Can you tell us more about the poems on Angel Island and how they traveled to the archives?

So, Him Mark Lai was a scholar, writer, community historian, and archivist. He was instrumental in preserving and translating the Chinese poems written in the Angel Island Immigration Station as well as documenting Chinese American history more broadly. Angel Island was a detention center where, from 1910 to 1940, migrants crossing the Pacific and particularly from Asia were held while they were interrogated about their immigration status. This was during the exclusion era which restricted Asian migration to the United States based on race, starting with Chinese migrants in the 1870s and expanding to all Asians by the early 20th century. The exclusion era legally ended in 1965 but its legacy continues to the present. Some migrants would be detained for years, others for just a few weeks, while they were interrogated to find out whether they were illegally entering the country. It really resonates with the attacks on migrants that are happening today.

One of the things that people did in the barracks while they were detained was write words and poetry into the walls which was seen as graffiti. At first it was written on the walls, then it got painted over. Eventually they started carving it into the walls and even with paint, you could still see the etches. I think they tried to putty it, do everything they could to remove it, but traces were still there. The detention center closed in 1940 and around 1970 there was a plan to demolish the buildings. At that time, a park ranger noticed the poetry and instead of moving forward with the demolition, he reached out to two San Francisco State professors, George Araki and Mak Takahashi, who photographed the walls and sparked a movement to save the buildings. The majority of the poems were written in Chinese but there were also poems in other languages like Punjabi, Japanese, and Korean. Him Mark Lai and a team of other people including poet Genny Lim and librarian and historian Judy Yung worked to translate many of the Chinese poems and started an oral history project interviewing elders who had experienced being detained there. They saw the need to preserve the building as a historical site of Asian American history and of American history in general.

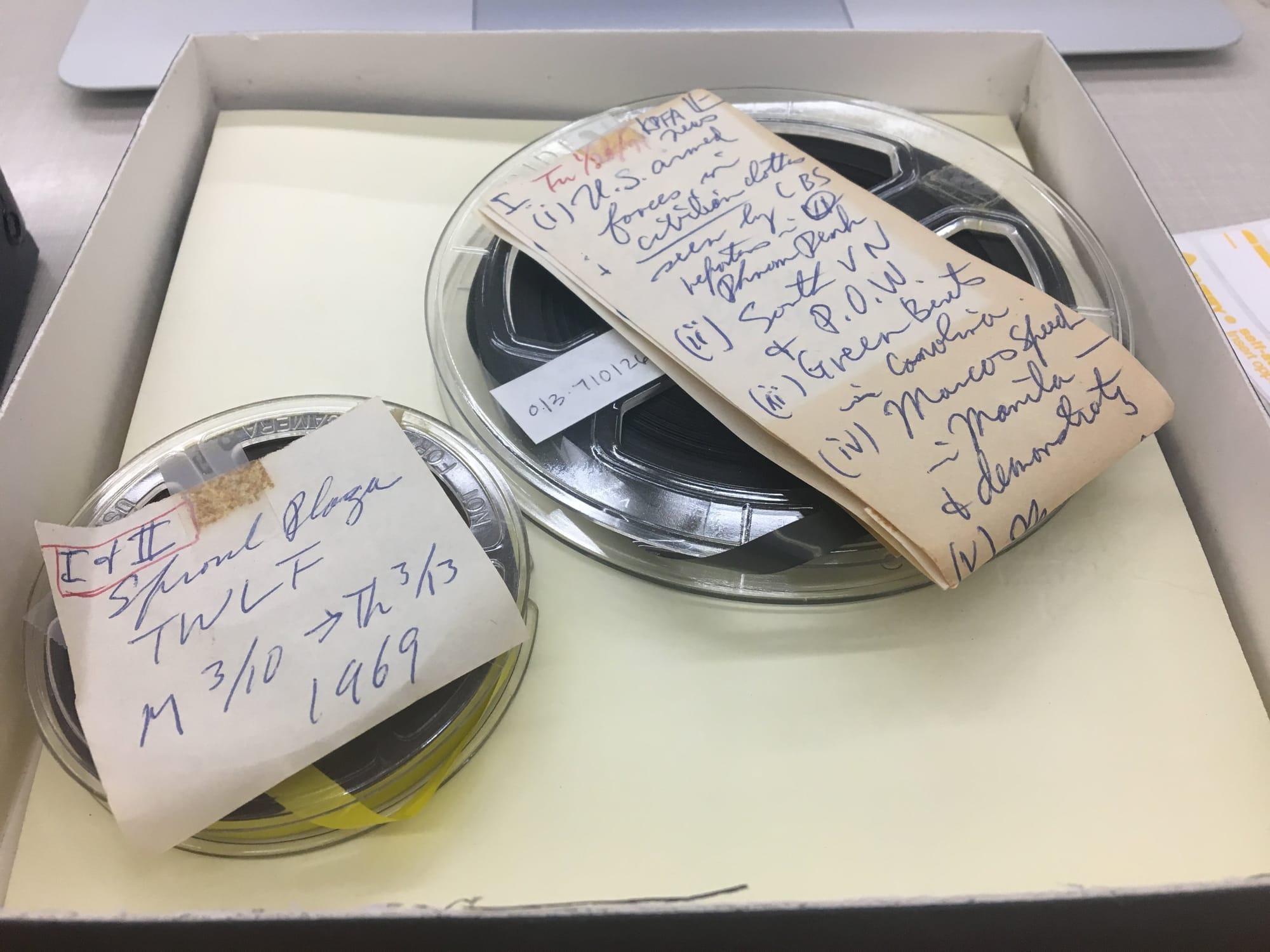

Some of the oral history interviews are preserved at the Ethnic Studies Library. In the 1980s they published a book of these poems called Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940. The poems also keep getting re-translated and re-visited over the years. Him Mark Lai was a big part of establishing the Asian American Studies archives at Berkeley too. He was born in San Francisco Chinatown in 1925 and felt a strong inclination to preserve history and write about it. He worked with and founded many community organizations, he would publish stories about Chinese American history in local newspapers and had a longstanding community radio program. At the time, there wasn’t much known about Chinese American history and from what I heard, he would talk to people in Chinatown or see that something was being thrown away and rescue it to be shuttled over to the Ethnic Studies Library. He also worked with the Asian American Studies librarian Wei Chi Poon. That's a story that is part of the origin of the Asian American Studies library and archives.

Were the poems carved in stone?

I don't know the exact material, but I think it was more like wooden planks that created a wall and so it was a little bit easier, maybe, to carve into than stone. And some would have been written on the walls too. But that being said, the detention center remains and the Angel Island Immigration Station has a museum now. So you can actually go see some of the poems on the wall.

Could you tell us more about Wei Chi Poon?

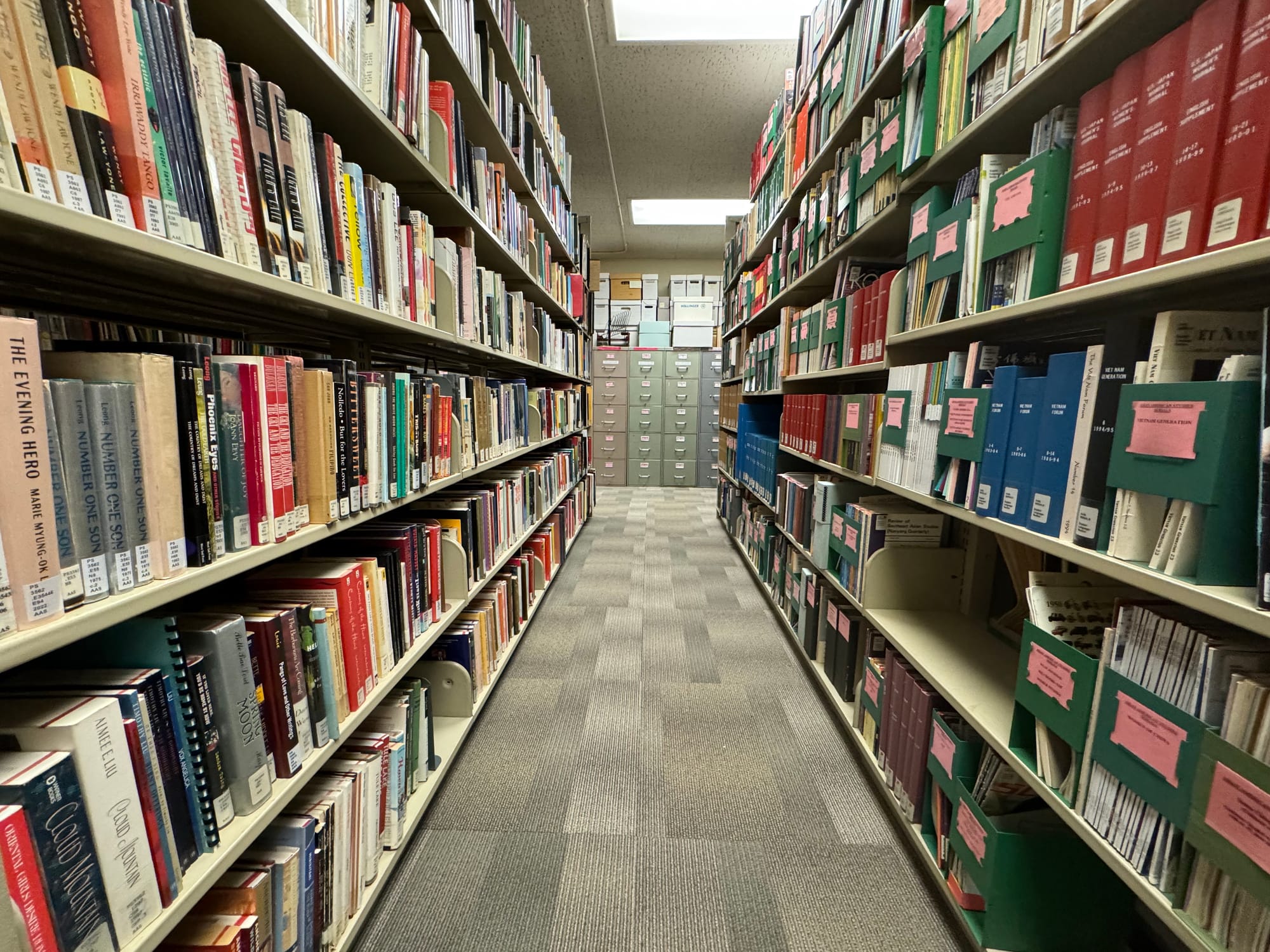

Wei Chi Poon was the Asian American Studies librarian at the Ethnic Studies Library from 1981 until she retired in 2014. She expanded the Asian American Studies archives and collection and made it accessible to researchers internationally. She helped preserve archives, books, magazines and other materials that documented Chinese American and Asian American histories and she put a lot of infrastructure into place at a time when Asian American Studies was still an emerging discipline. She also wrote a book called A Guide for Establishing Asian American Core Collections in 1989 that could be used by mainstream libraries to help build their collections. She retired in 2014, I believe, and sadly, she recently passed away in 2025. She created the foundation at the library that I and so many others still benefit from and build upon to this day.

You sent me a link to the Berkeley Revolution digital exhibit, which tells some of the story of the creation of the Ethnic Studies department. It strikes me how much revolutionary spirit and collectivity is in its history. I’m curious about who all the people are, the different groups of people, who contribute everyday to its making.

It’s vast. I think of the Asian American Studies collection and the Ethnic Studies Library as a living archive and to me, it’s really important that it is part of a broader library that also focuses on communities of color. You mentioned craft; it’s also a praxis that I feel I've been learning over the last 10 years at the library. I'm very aware that the way archives have been shaped is based on colonial record-keeping and state surveillance. It follows the Western approach to history, which until recently has tended to privilege the perspectives and writings of those who are in positions of power. That is a long history in and of itself, but when I think of the living archive and the Ethnic Studies Library, it has a history that is rooted in collective struggle. It's living and breathing in the community itself. What that means to me is that we are all holders and carriers of history. Each person carries a piece of it, and the connections are infinite. It feels really different from traditional archives where a lot of what you may find is from the lens of outside perspectives. The Asian American Studies Library was first formed by students and activists like Lillian Galedo and that tradition continues. People may visit the archive and they'll look at something and they'll say, oh, my gosh, that's my aunt and then they may go talk to their family member about it and maybe decide to bring some magazines or photographs to donate to the library. All of these artifacts created over the years, some fragments make their way to the archive—but the true archive is really within the people, community, relationships and memories and the library is one reflection of that. Does that make sense?

Yes, absolutely. I’m reminded of Stuart Hall, who wrote about the term “living archives." He said, “Constituting an archive represents a significant moment, on which we need to reflect with care. It occurs at that moment when a relatively random collection of works, whose movement appears simply to be propelled from one creative production to the next, is at the point of becoming something more ordered and considered: an object of reflection and debate.” Does this resonate with you? Are there such points of becoming, propulsive edges and geographical coordinates, at which the Berkeley archives are growing?

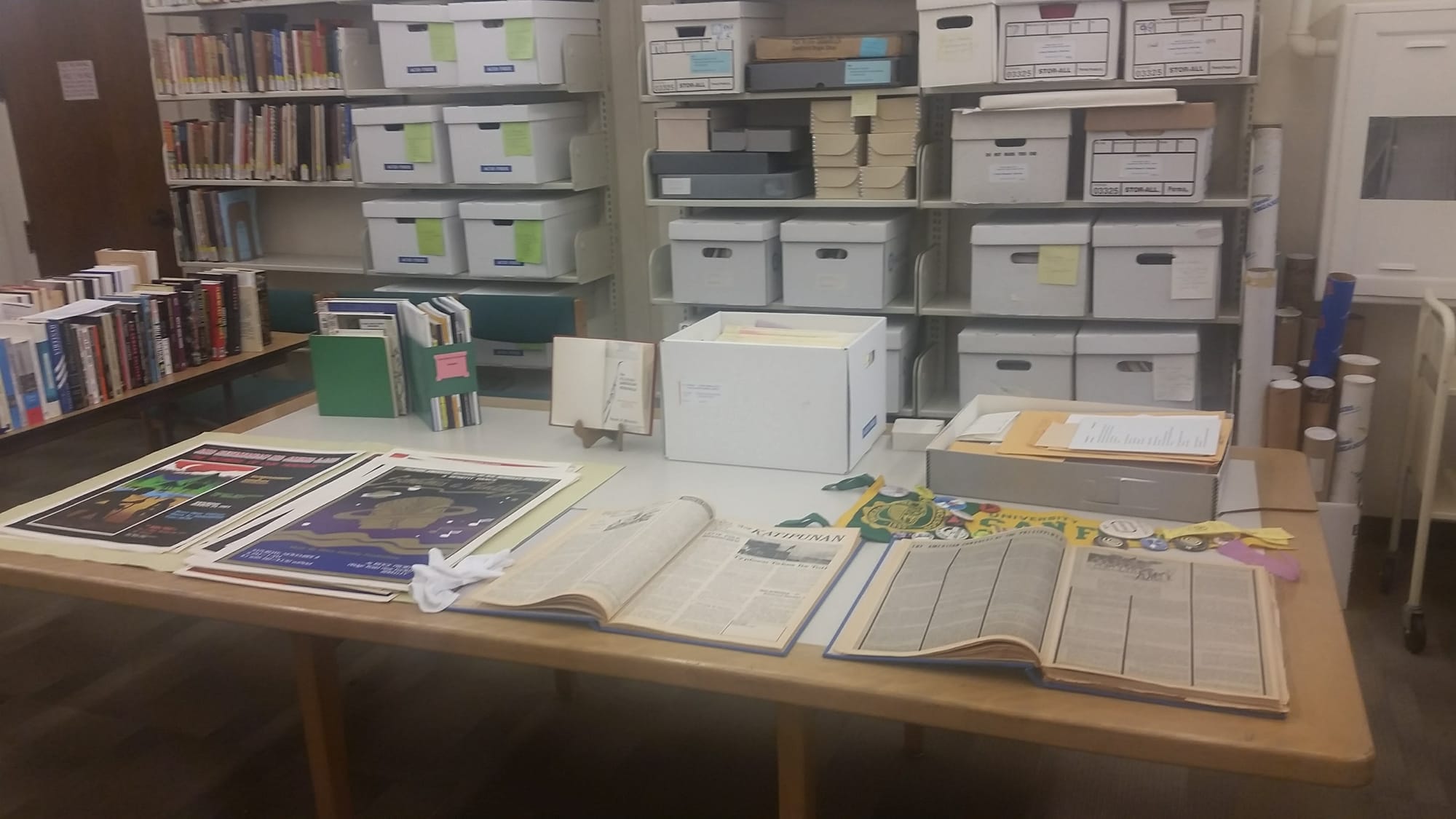

I envision the library as a nexus of all of these threads and cords and connections across time and space and relationships. And as far as the moments where objects become archives, that process can be really fluid. A lot of times, it's as simple as people reaching out with materials that they found in their house or their family members' archives. Or maybe someone has recently passed and their community and family are trying to find a place for their archives and books. Sometimes people send things in the mail, or come by and drop things off at the front desk. Some of them want to be recognized as the donor. Others don't want to be recognized. They just want to know it will be preserved for future generations.

Then there's all these library processes that describe and make things visible. A big part of it is processing the archives, going through every single box, every single file, and making sure everything is safely stored and organized and that private information is protected. Then there's the cataloging of it, making sure it's entered accurately and in detail into online catalogs so that people can actually search for and find them. We can have all these amazing archives, but until this work is done, it won’t be accessible to people. If an archive is only known to a few people, or if it’s not possible to visit, it’s not really accessible, right? If it’s not preserved and maintained with a sense of looking very far ahead in the future, it may only be available for a few years. All of these processes take a lot of time and at each step, there are ways in which one’s knowledge, lived experience, and bias can make a big difference.

Then there’s all the work day to day to keep the library open and helping people visit and navigate the archives. Talking to classes and researchers or creating exhibits so people know what kinds of resources and archives they can access. I think one of my roles as the librarian is to hold a bird’s eye view of all those processes and connect the dots where I can.

How did you learn to navigate all those processes? What was that journey like for you?

It's definitely been a lifelong journey. When I look back to the reasons I felt compelled to go towards the library and archives world, a lot of it had to do with being kind of a family archivist in my own family, seeking answers about our history and trying to grasp at what felt like sand slipping between my fingers, of history in a diasporic family with roots in China and Southeast Asia, in a family that has a refugee history. Trying to piece things together. Why are we here? What happened? Why aren’t stories like ours in the books I’m reading at school? I often felt and was treated like an outsider and wanted to understand where I belonged. As a young person, I started working with my grandfather, my Gong Gong, for many years on writing his life story down and I feel like working with him was the early days of forming what archives meant to me.

But being at the library is on another level. I think a lot of learning to navigate these processes comes from experiential knowledge and learning from the guidance of others. I learned a lot from other librarians and archivists when I worked at places like the Asian American Pacific Islander Collection at the Library of Congress and I learn from my colleagues at the Ethnic Studies Library all the time. I learn from research, talking to all the different people that visit the library, practice and making mistakes. There's a lot of things you could learn on your own, but in relationship with someone who can provide some guidance, that opens up so many more doors and directions for you to go. Having guidance or just accompaniment makes such a difference and it’s something we don’t always have access to when we are part of marginalized communities or first-generation students.

What was it like working on the project with your Gong Gong, and were there people who guided you there?

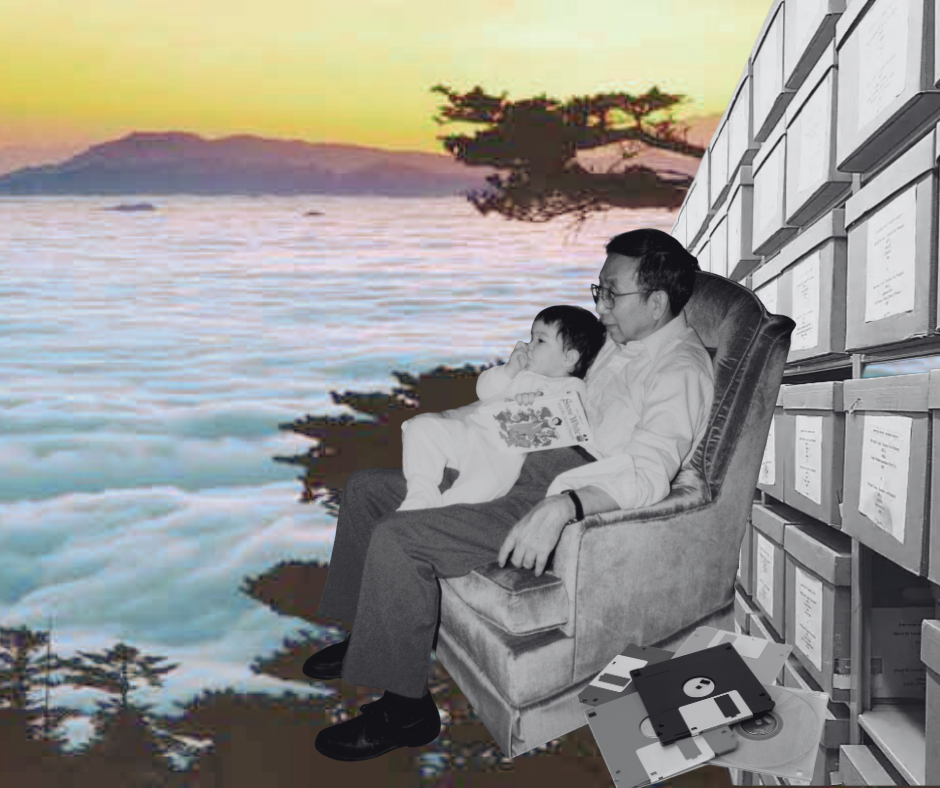

One of the reasons why I started working with my Gong Gong was to keep out of trouble. My mother was a single parent who had come to the US at the age of eight. My father passed away when I was young. I had a rebellious and unsettled spirit and the idea was for me to live with my grandparents and help them with things. I don’t remember being excited about the idea at first, but I had no idea how it would later shape my whole trajectory. My grandfather decided to write down his life story in English for future generations and he had me edit the text. He would write and I would edit, and we would pass floppy disks back and forth. I didn’t have a strong writing background and I didn't have a lot of guidance as far as what I was doing, but we just figured it out as we went along. I was really proud to be part of that and I learned so much. My family may not have always been very forthcoming about our history, probably because it carried a lot of trauma, and of course, everyone had their own perspectives or memories of what happened and did not necessarily agree. Maybe the idea was to leave the past in the past. We don't need to talk about it or burden the younger generations. But for me the past felt very present and working with my grandfather helped me understand more about the way my family was, what they had been through and therefore, how they came to be the way they are.

Are there qualities of your Gong Gong that still inspire or inform your work in the archives today?

There's a picture of him giving me two thumbs up on my desk at the library so he’s definitely always with me. He wasn’t perfect, but he encouraged me and he was the kind of person that would have me come as a little kid back into his den and sit me in front of him and we would exchange stories. I remember my grandfather being someone that might just let me talk and go on and on and tell my tall tales and imaginary stories. He had a lot of stories to tell me too and I loved to listen to them. My imagination could run a bit more free with him. And that space that he held for me is something that I cherish and try to bring into the library—the space to imagine, to be curious and feel confident in learning, sharing and exchanging. During the process of helping him with his writing, I also learned that sharing stories and deepening our relationship was as, if not more, important than the final book itself, and I have definitely kept that lesson in mind as well.

What does it mean to you to be a librarian, or work in a lineage of librarians? What does that word mean to you?

For me, the best parts of librarianship are about learning, connecting, and cultivating a sense of belonging and curiosity in history and in the world. Getting to meet and support people in the process of learning or creating something, learning from them—that's one of the fulfilling parts of being a librarian. There are endless paths of creativity and inspiration that one can follow and that touches on a sense of wonder and curiosity that I really enjoy. I think the deeper thing for me is that the library has always been a safe place and sanctuary for me, especially around being neurodivergent. When I’m curious about a topic, I’ve always enjoyed researching and have lots of sparks of ideas and connections. But at the same time, my thought processes were always different from most of my peers. The library was a space where I could imagine and be in my own world. It's always been that kind of a sanctuary. So cultivating that kind of environment for others, it means a lot. It's very fulfilling. Both of my grandparents on my mom’s side also worked in libraries, so I definitely am following in their footsteps. It’s a familial sense of lineage but also a broader sense of lineage, getting to be a part of the bigger project of preserving histories that might otherwise be lost or forgotten.

I wonder how being neurodivergent informed the question of the work you wanted to do. Did you struggle with linking that dimension of self-knowledge to what you wanted to devote your life and labor to? Is that something that came very quickly and naturally?

I definitely struggled. I’ve always felt drawn to libraries and archives and there are ways that being neurodivergent for me align with the work of being an archivist or librarian. But it was a pretty winding path. School was always challenging. I originally pursued the sciences, but I was politicized in high school and college during the Iraq War and around issues of racism, labor and feminism. I had worked in the special collections library in college and at a radical bookstore and was drawn to archives, literature and political education. I realized that working as a scientist didn’t appeal to me. After a few years, I decided to explore the possibility of working as an archivist. After having lived with a lot of instability and working a lot of jobs from auto mechanics to food service, I felt like working in archives was potentially a way towards more stability but also a way that I could be in an environment I enjoyed while putting my radical values into practice. I think what I perceived as more quiet work in the archives appealed to me too. I didn’t have much of an idea of what I was getting into or that being a librarian would be so different from archives work. But coming to the Ethnic Studies Library was exciting because it brought together so many of my passions and interests. It wasn’t something I imagined was possible.

Now that I’ve worked as a librarian for more than a decade, I’ve also experienced how challenging the work can be for neurodivergent people and people with disabilities, like myself, especially at universities where you encounter a lot of intellectual ableism. It's been a long process of learning from experience, growing and pivoting as I learn more and continue to evolve. And now that I’m at the library, the collection evolves along with me. It's very dynamic and organic. Even though the archives are imagined as this space of stillness or quiet, working there can be completely different in my experience. Even on a quiet day, things are constantly circulating, needing to be done, people coming in and out. At the end of the day, while I do enjoy working in the library, it’s important to recognize the difficulties too and that work isn’t the only way we should define ourselves or value our productivity.

Berkeley is one of the more well-known institutional archives for Asian American Studies. Do you interface with a broader community of librarians who work in Asian American studies and archives?

Definitely. There are many networks, community organizations and collectives, so many different groups who are working in different ways on memory keeping and archives. Professionally, there are groups like the Asian Pacific American Librarians Association and the Association for Asian American Studies where librarians and archivists connect. In the University of California system, the Ethnic Studies Library at UC Berkeley is one of several libraries with an explicit focus on Asian American Studies alongside libraries and archives like the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, the UC Irvine Southeast Asian Archive and the UC Santa Barbara California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives. There’s a collective knowledge sharing group around Ethnic Studies for librarians and archivists in the UC libraries and there are many librarians at other universities or in public libraries that focus on Asian American communities and materials. I find that librarians and archivists, even though they are usually very busy, are generally open to collaborating, sharing information, and helping each other. There are Asian American archives in so many places like universities or historical societies, community archives and museums, digital projects, or people's homes. But having an Asian American Studies collection that has a physical space where people can visit and a dedicated librarian is unique and important. We're able to devote more time and resources and have more specialized and focused knowledge. At most archives or larger repositories, Asian American archives or materials are usually subsumed under a large number of broader categories, so it may not get as much attention.

There’s also a community of librarians, archivists and memory workers who are attentive to questions of justice and repair. The term reparative archives has become more well-known these days, it’s essentially working to repair the harm that's been done to marginalized communities within libraries and archives. Some examples of spaces that come to my mind are the Radical Libraries, Archives and Museums space at the Allied Media Conference in Detroit, Michigan and more recently the group Reparative Memories: Communities in Crisis and Archival Care led by professor and archivist Thuy Vo Dang and professor Crystal M. Baik at UC Irvine. These spaces are really important and generative and it’s critical to have collective spaces to think through these huge issues together. No one person can figure it out or do it all alone.

But a lot of times in our everyday work, librarians and archivists on the ground do have to just figure it out and make the best decisions that we can, document why we did that and learn from our mistakes. Maybe a year later we would look back and say we would do things totally differently. But time and history keeps moving and evolving and archives and books and materials keep coming in. There is a level of just needing to do the best we can. Especially in academia, there can be a really strong drive for perfection that I’ve found, through experience, can be a barrier to the work.

What's an example of a difficult decision you've had to make?

I’d say some of the most difficult decisions for me sometimes come up around deciding whether to accept an archival donation. It can feel fraught especially if people are reaching out with urgency, but there is also a lot of labor and space that is needed to preserve and make archives accessible long-term. Sometimes it can be really difficult to decide that we can’t accept a collection, but in those cases, I might try to connect folks with other people or places that they could reach out to. That has gotten easier over time, but it's always difficult, because there is a great need. There’s this sense of urgency and immensity to the archives world, a sense that there are an infinite number of archives that need to be preserved and we can only do our small part. Probably those are some of the hardest decisions. But I always remember that the Ethnic Studies Library and any library or archive is just one part of a vast ecosystem of libraries, archives, museums, and community centers. It’s not about trying to collect everything, which to me comes from a colonial way of thinking about archives. It’s about knowing what our strengths and capacities are as a library and making sure we are responsible stewards for the collections we do care for because overwhelming our staff or library space can also lead to eroding care for the library and collections as a whole.

I was looking at the Ethnic Studies library page, at the paragraph which starts with, "Today the term Asian American is more often used as a demographic marker" and then it speaks to an expansive and inclusive approach in the collection—what’s included, excluded, the bounds of Asian America and the ways in which AAPI or API can be problematic where it excludes and marginalizes experiences. What does archival harm or repairing harm look like in the context of the evolution of “Asian American”?

It’s important to acknowledge biases and marginalization within Asian American Studies as well as the tensions within and between our communities. For example many narratives or collections have not been intentional about representing South Asian, Arab American, or Southeast Asian communities. The terminology of “AAPI” or “API” is often used in ways that ignore or marginalize Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities. Sometimes there can be romanticization or essentializing that can make it difficult to be critical of power dynamics within our communities and in our ancestral homelands. There are juxtapositions between the politics and perspectives of different generations. There are inequities and dynamics like in any community along lines of class, gender, religion, or nationality. I try to be mindful of these dynamics though I will always be learning, and do what I can to acknowledge that the library is a space that isn’t perfect but where we can have those conversations. It's not about being perfect, but about being in relationship with each other, even, or maybe especially, when it is messy. At the library, I try to take an expansive approach to the Asian American Studies Collection which is different in some ways from how the collection was approached in the past. It’s been something that I've put a lot of intention into while I’ve been the librarian. It's ongoing and in any archive or library, it's like every year is another layer on top of another layer. You can’t really go back and change things, right? History doesn't work that way either. So you just keep making the best decisions you can, making changes when you can and acknowledging what was done before. You can always choose to go in a different direction, but the foundation always informs the work that you do.

One of the things I've learned about the history of the term “Asian American” was that it was rooted in a vision of coalition, solidarity and collective liberation. It came out of the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) in the 1960s and replaced the term “Oriental” which was still widely used. The formation of AAPA and the coalition with Black, Chicano, and Native students to form the Third World Liberation Front and Ethnic Studies was very connected to the formation of Asian American Studies and the library. Specific communities, primarily Chinese, Filipino and Japanese communities, were part of creating that framework of solidarity between Asians and with other communities of color in the 1960s. Things have evolved in so many ways since the 1960s and the exclusion era, especially in terms of migration. Most people, especially first generation migrants who make up the majority of Asian Americans today, would probably define themselves more by their specific nationality than as Asian American. There are a lot of stereotypes or different ideas of what Asian American means. You might technically be part of the same demographic group or from the same continent, but you may not have a sense of solidarity or belonging with others. There's a constant tension that I think is pretty normal for people and communities between the ways we identify and the ways that others identify us. There's so much fluidity and evolution in terminology and history and I think it’s important not to get too fixed and rigid but rather allow for multiplicity.

At the library, I feel it's important to touch back to that original sense of solidarity and coalition. Since the early days of Asian American Studies, the way people may view the term Asian American has really shifted towards more of an identity or a demographic as opposed to a political vision. The American cultural imagination of Asia is also so narrow that it can constrict our imaginations. Oftentimes people might make the assumption that there probably isn't anything in the library for them, or they might have a negative reaction to the term Asian American. They may not know what the library considers part of Asia or not, because those ideas are fluid and have changed over time too. But really, the library is a place where all kinds of contradictions coexist, just like in the world. I try to just make it clear that it's a space where you can take what’s helpful and leave what’s not and that by having conversations, you can be part of shaping it too.

When I heard you speak at the “Building a Queer and Trans Pacific American Living Archive” at the AAAS conference in Boston, I remember how you gestured to the real abundance in the archives—so many boxes, right? You said people come and are often surprised at how many boxes there are.

I think there's a real sense of historical erasure that many of us carry and I see that a lot with people who visit the library. They've often been told there's no archives about their community. They might do a search and nothing comes up, because the terminology used by mainstream or academic archives can be so different from what folks use themselves or because archives didn’t feel that it was important to collect those materials. That's a very insidious way that our communities have been robbed of a sense of history and connection and lineage. There's never been a time in history where people haven't communicated or expressed themselves, whether written or spoken or sung. But there were so many reasons why that knowledge was not valued or was seen as a threat, so it was either destroyed or not preserved in the ways it should have been. There's a real sense of loss there, it's the grief that we build our hearts around and it's a grief I feel is carried by a lot of people. Sometimes it shows up in that way of just being shocked when there's actually this abundance of knowledge and archives. When people find that there is actually an abundance of archives and resources if they know where and how to look for them, it can be overwhelming and healing. Oftentimes, people can’t imagine how long it may take to go through a box of papers or an entire archival collection and then they realize that they could spend days or months or years finding and learning from just one archival collection.

I also don’t think people often think about the physicality and labor of archives. Boxes of books or papers are heavy! And when you have dozens or hundreds of boxes, there is a very physical aspect to the work of archiving and even making things accessible to people that includes lifting and moving. I think many people don’t often think about it because they are thinking more abstractly about archives but I think about it a lot as a disabled librarian. I think the labor of archive and library work is something that needs to be centered, especially in academia where labor and wellbeing are often overlooked.

Are there particular underrepresented communities or stories that the library is currently actively looking for to be more represented in the archives?

Being queer and non-binary myself, I feel a personal call to document queer and trans communities, especially within this political climate and because sometimes our movements have been marginalized by broader left movements. Archiving and documenting is a way of creating a kind of permanency and affirming existence. You met Trinity Ordoña at the AAAS panel, and her archival collection at the library is part of that. Before I started, the library had already been collecting books and different newsletters or magazines like Phoenix Rising, Trikone or Lavender Godzilla. Trinity’s collection brought a new dimension and she also established the Queer and Trans Ethnic Studies Library fund which will support work in the future. In general, I tend to look for archives of resistance and activism and communities which may be underrepresented in the library or that don't always get the same kind of attention when it comes to archives. I try to support people or organizations working on archiving when I can as sometimes there is a precariousness that can make archiving even more challenging.

Do any recent examples come to mind, how precariousness affects the way that things get archived or not get archived?

I think it always comes down to our lived experiences in the sense that having the time, space or capacity to devote to archiving is dependent on our survival and wellbeing. Sometimes I work with elders and people who are trying to preserve their own archives and they may struggle with having the time, health or the physical space to be able to organize things. When you're working on donating archives, issues of displacement and housing, financial stability or disability come up. People might have to move suddenly or they don't have the time to be intentional about deciding what should be included or not included. So you just need to figure out how to pick up those 30 boxes as soon as possible. When people are struggling with surviving, the idea of archiving can seem like a luxury, because you're in survival mode. Activist communities can have that issue too. A lot of the work is in reaction to urgent issues and the idea of preserving things, even though people have this really strong intention to do that and they love archives and history, the actual time and space to do that labor of renaming all the files in your Google Drive for example, that's hard. Who has time for that? It’s something you dream of doing and sometimes people are like I'll just take a day and do it and then they realize I need months or years to do this, because it's such a long process. People are busy living, surviving and organizing, and so preserving archives and doing all the labor that is entailed in that is often secondary to survival. Another thing I notice is that sometimes our elders may not realize the value and importance of their archives and stories. They may think, who cares about this, I just did what I had to do to survive. But, to younger or future generations, those stories may be precious ways of understanding ourselves and our histories.

If there are any activist communities or organizers who are reading this interview, as a librarian, are there any tips that you would give them, such as how to develop an archiving practice, or best practices to keep in mind; are there even small things they can do that really help with archiving later down the line?

The biggest thing is resist perfection and do what you can. That seems to be a theme. A lot of people don't start because they know they don't have the time to do it the perfect way they would like. For example, if I have a box of flyers, I might have this yearning to digitize and document every single flyer and label it and organize it. All these steps. But I may not actually have the time and capacity to do that, and so it might be just good enough to make sure that those flyers are flat, and in a box labeled “flyers” with the date so that I can get to it later. I think a lot of times we don't know what to do with all the things that we've picked up. I struggle with that personally. So just finding a way to keep things safe for a time when you are able to make a decision, I think is the most important thing.

I think it's also really important that activists, artists and others know that it's so important that they be the ones to tell their own story. Oftentimes we're doing things, but we don't necessarily focus on creating the narrative about it. That's where you see researchers or people who may not have been involved trying to look through archives to piece together the story and sometimes getting it wrong. So if there is time, write down what happened, even if it's a journal or a diary, or record interviews or oral histories with each other. We really have to take a very active role, if we can, in documenting our own lives on our own terms. Because otherwise others will either do it for us and might get it wrong, or not do it at all because they don’t see the importance and the value. We are the ones who know the value of our work so deeply. This is one of the reasons why I gravitated towards making zines as a young person too because it was an uncensored way to tell and document our stories.

That's awesome.

Yeah?

Yeah. An uncensored way to tell and document our stories. And remembering it is us who know the value of our stories so deeply.

Yeah. And that's a real thing also, because a lot of the folks I’ve talked to were and are really focused on the collective. They wrote for the newspapers, they wrote essays or poetry, or they created artwork, but they didn't necessarily feel like it was the work they were doing as individuals that was important. They felt like the movement was important. The collective was important. That's a really beautiful value that a lot of people have around collectivity. But I do see that also reflected in the archives through a kind of self-censoring, or self-erasure. It's like, oh no, don't put my name on that. No need. Sometimes you have to be concerned about surveillance, and so there's safety questions, or you just prefer to be anonymous which is always okay. But sometimes you see people minimize their role or stories because they don't see the value in their work or contributions. They just feel it's more important to see the collective, and I get that. But we are all a part of the collective and you should be recognized for the work that you did if you feel safe and comfortable to do so.

Earlier, you were talking about queer and non-binary and trans stories, and you mentioned tags in particular, and I was thinking of this kind of queer excellence related to imagination and invention of language and terms, and I wonder, do you see an evolution of Asian American queer language or languages throughout those archives? How is language a fluid thing throughout the stories told and moving over the years?

It’s a huge conceptual question that is so critical in day-to-day library and archive decisions. Classification systems are systems that were created to basically sort and organize and categorize books into different subjects like history, technology, medicine, etc. There's two big classification systems that are often used in American libraries. You’ll see the Dewey Decimal classification system at a lot of public libraries, and the Library of Congress classification system at academic libraries for the most part. These systems emerged in the late 19th century when there was this codification of difference around gender, sexuality, race, and other identities that we still grapple with today. There was an emphasis on Eurocentrism in terms of what subjects and authors were considered more important. Library systems were created with all of these biases imbued in it and it affects how knowledge is organized. The Library of Congress also maintains a set of terms or subject headings that most libraries use in cataloging and describing materials. You could think of these terms like tags that allow people to search for and find materials.

In the library world, there is a drive towards standardization of language. On the one hand, standardization can enable searching across a lot of different systems using the same term. But standardization comes up over and over again as something that we just can't always make work with the way that people identify and the fluidity of the language that we're creating and inventing and remixing and that is especially true for queer and trans communities. For example, I don't think the term “queer” is officially approved within the Library of Congress. I think the term “sexual minorities” is the subject heading that is in use. But how many people who identify as queer would identify as a sexual minority? Homosexuality used to be defined in relation to mental illness so if you were trying to look up information using the term homosexual, you would have been redirected to works about mental illness, and all kinds of different terms that were negative, derogatory, or pathological. The Library of Congress tends to follow state or academic definitions and terminology so we often add our own, what we call “local terms” at the Ethnic Studies Library, to supplement. We want people to be able to use the Library of Congress terms, but we know that that's not the only way people may be searching for things. A lot of things get lost in the sauce because people are searching for them using words that they're familiar with, and it's not connecting with the words that have been used in the library or archive. So you may search using the term “nisei” for example but materials are labeled “Japanese American” or you use the term “queer” but a book has the subject heading “sexual minorities.” Often traditional librarians and catalogers are limited to using the terminology from the Library of Congress so it’s important that the Ethnic Studies Library be able to use local terms and accept that there is multiplicity and fluidity in the ways people identify. That terminology is not neutral and people have reactions to it, it carries meaning and histories.

Wow. So what if you want to add something or see it added to the Library of Congress terms?

There's a whole process where you have to create a proposal, and you need to cite authoritative or scholarly works that use this term as evidence for why this term is legitimate. That in and of itself can carry a lot of problems. Even if the term is not referenced in an ‘authoritative’ work, the term could still be legitimate. It still exists and is in use. So there can be a disconnect. The Library of Congress process for adding terms, it does happen, and there are librarians who have devoted a lot of time and energy and have made significant changes which have made a huge difference. But sometimes at Ethnic Studies Library, we take this different approach where we add local terms to the catalog record. There can be a lot of resistance to that idea. People may ask, how long will these terms even be in use? There's an ephemerality to it that people kind of ascribe that can be delegitimizing. Like, this might be a fad, it's not serious. However, it is still important to use terms that align with the way communities identify themselves if possible to enable them to search for and find them.

Also, sometimes the collective knowledge across librarians about Asian American Studies can be quite low, unfortunately. So catalogers might not know what are the best terms to use and so they follow what has been suggested by the publisher or what the Library of Congress provides, and they have so many books they have to catalog in a day that for the sake of time, they do the best they can and just move on, right? It's not always malicious, but it's a lack of collective knowledge and the awareness, time and intention to really think through what are the words that are missing here and what will the community be looking for that are not going to bridge with what terms I'm seeing here. You have to dedicate time to learning about these things and often talking with people to find out how this plays out within community, and about what terms researchers might be using now. So it's really dynamic. I’m grateful that the Ethnic Studies Library is open to this creativity and multiplicity around language.

What you say also seems like an opportunity for librarians and archivists to work together with scholars and students and community members, within and against this apparatus of power wherein terms gain currency through being legitimated by scholarship.

Working with scholars, students, and faculty and learning from the community is definitely an important part of this process. There's a really good documentary called “Change the Subject,” about a group of Dartmouth students and the movement to change the subject heading ‘illegal aliens.’ That’s one example, but librarians, archivists and scholars collaborate often in order to improve systems.

So many languages are spoken in the Asian American diaspora—do the local terms also reflect that multiplicity of languages? Will you see Chinglish, for instance, in the local terms?

That’s an interesting and important question because many Area Studies libraries are limited to collecting in particular languages and sometimes the beautiful messiness of the diaspora can get lost. For the Asian American Studies Collection, we collect in different languages, as long as the subject or content is about Asian American or Asian diasporic communities. But that presents a big challenge because there are so many languages as you said and we don't always have staff that can catalog or translate these materials. So we often have to work with other librarians or catalogers, student employees or volunteers to do the best we can. I do think it's important that we not have that language restriction, especially as you said, because there are languages that are not officially recognized, like Chinglish or Taglish. The issue of language also touches on authenticity and voice, and the library tries to make space to affirm the realities of experiences and different voices in the diaspora as opposed to creating barriers that are too rigid to encompass the kinds of archives and materials that are important to preserve.

Yes, when we emailed, you specifically pointed me towards the Bibliopolítica exhibit.

The Bibliopolítica exhibit tells the story of the Chicano Studies Library, which also came out of the 1960s and has been led since the 1980s by Lillian Castillo-Speed, the Chicano Studies Librarian and current head of the Ethnic Studies Library. It merged with the Asian American Studies and Native American Studies libraries in 1997 to create what is now the Ethnic Studies Library. Prior to that, each of the libraries were autonomous reading rooms. The Bibliopolítica exhibit highlights the ways that the library workers of the Chicano Studies Library were creative and forward-thinking, especially around language and terminology. They said, well, if the Library of Congress doesn't have the terms that we need, we're going to create our own thesaurus or ‘controlled vocabulary’ called the Chicano Thesaurus. They published the thesaurus so that catalogers and other librarians could use it when they described and cataloged Chicano materials. They did so much work to create those library foundations for Chicano Studies materials, even creating new classifications that diverged from the Library of Congress classification system that are still in use in the Ethnic Studies Library today. That exhibit talks about these issues of language and cataloging and also about technology, how they evolved to CDs and to digital. The exhibit is a really good example of ways that you can use archives to tell a story and it is a really beautiful tribute to all the work that was done in the Chicano Studies Library.

Do you accept volunteer community translators, is there a big process to go through if you want to translate for the archive?

Sometimes we consult with other librarians or we have student employees that help. Sometimes people who do research at the library are willing to share their translations with us too. We do accept volunteers and it isn’t a huge process, but sometimes we are limited by how much capacity the library has to work with volunteers given our small staff. We always appreciate when people are interested in helping out at the library.

Sine, thank you so much for sharing your time and knowledge with me today. Is there anything you want to leave us with?

Well, I guess I’ll just reemphasize how important it is that we be the narrators of our own stories, the importance of solidarity, of resisting erasure and scarcity and remaining open, curious and determined in searching for and documenting our histories. When we move from a place of abundance and confidence in our own ways of knowing, I think it’s possible to regain some of our power within a system that devalues and delegitimizes our knowledge and wisdom. That power is so necessary, especially in these times. Thank you so much for the opportunity to talk with you!

Winona Guo is a PhD student of Asian American literature at Columbia University, and author of Tell Me Who You Are (2019).