Nellie Wong is a poet and activist living in San Francisco. She is the author of five collections of poetry that span from 1977 with the publication of Dreams of Harrison Railroad Park to her most recent collection, Nothing Like Freedom (2024). Wong co-founded and organized several feminist literary collectives, including Unbound Feet (with Kitty Tsui, Merle Woo, Nancy Hom, Genny Lim, and Canyon Sam) and The Last Hoisan Poets (with Genny Lim and Flo Oy Wong). A socialist and a feminist, Wong is also a longtime member of revolutionary socialist organizations, Radical Women and the Freedom Socialist Party.

I first learned about Nellie Wong at a poetry event in 2019, when, during a Q&A, an older poet lamented how no one seemed to know Nellie’s work. A poet from an earlier generation, Nellie seemed to be at risk of being forgotten, as Asian American poetry becameomes an increasingly prestigious and acclaimed body of work in the 21st century.

I was one of those uninitiated, so I began to do some research: I bought a used copy of The Death of Long Steam Lady, ordered a DVD of Mitsuye & Nellie, Asian American Poets, and learned what I could about her life as a poet, an organizer, a feminist, and a secretary. All of these roles—poet, feminist, worker—came together in what I would describe as a poetry of lifelong commitment: to living a Third World, feminist, and socialist life, and to writing a form of poetry brought all these identities together.

I met Nellie in January 2023, where she generously invited me into her San Francisco home for an interview. Over hot tea, I spoke with Nellie about how she became a poet and an activist. A few months later, over Zoom, I spoke with Nellie again to continue our conversation about her political development through her involvement with socialist feminist organizations. We also talked about her close comradeship with other Asian American poets-activists like Kitty Tsui and Merle Woo, and her 1983 trip to China with Tillie Olsen.

Tell me how you got into writing poetry. What drew you into poetry in the first place?

I was working already. I'd been a secretary, an administrative assistant, and an affirmative action analyst when I was working. I went to San Francisco State in the early 1970s, after I’d already worked many years. What got me to go to college finally were a couple of things. My younger sister, Flo [Oy Wong], an artist and poet, said that I should take up writing. I asked, “Why”? She said, “Because you’re kind of funny.” [laughs] “Your newsletters are really funny. You should take up writing.” In those days, we didn’t have computers or phones, so I would write to my siblings to tell them to bring this or that for Thanksgiving or Chinese New Years.

Flo also said, “you also watch too much TV. You should get off your butt.” [chuckles] “Okay,” I thought, “Maybe I will do that.”

I signed up for a class at Oakland Adult Evening School. It was on short story writing. The teacher liked what I did, and every week I would raise my hand, I would have something to say, and I was writing. One of the first things I wrote was about my father. I think I wrote it as a parable. At that time, I didn't even know what a parable was. [chuckles] Each week I would write and turn in something. The other students were all adults, and it was only five blocks from where I lived in Oakland.

I was also working at Bethlehem Steel at the time. At work, there was an educational assistance program. The education assistance program was there to help us to do our jobs better at Bethlehem Steel. So I signed up, and my supervisor okayed all the courses I signed up for. I signed up for Asian American Studies. I signed up for Feminist Studies. I signed up for Creative Writing and English Literature. Here I was, already in my early 30s, and the classes that I took, I could only take at night because I worked full-time. That's what got me started.

I also signed up for a poetry class. I was very naïve, and I thought, "I'm interested in what poetry is. I don't know anything about it. So I'm going to sign up for this class.” But then, I found out it wasn't to study other poets. It was to write poetry. I was too scared at that time to drop out, because I’d worked so long to get to college. On the first day, the professor said, “People with last names between A and D are going to read next week.” I said, “Read? Read what?” [laughs]. We were supposed to read our own writing! I’d never written anything.

So I wrote. I was married at that point, and living in an apartment in San Francisco. I told my then-husband, "Leave me alone. I'm going to write a poem." [laughs] That's how I got started. I wrote some poems, and I took one to class the following week. My married name was Balch, B-A-L-C-H, so I was one of the first student poets to read. I read one on Miss Chinatown, USA. It’s called “Drums, Gongs.” It was in my first book, and eventually published in East/West [Chinese American Journal], an English language newspaper that came out of SF Chinatown.

After I read, the teacher said, “Once you've written angry poems, you should throw them away.” I was just mortified. I wasn't speaking up in those days. I told some other students in my feminist studies classes, and they said, "You don't have to listen to him.” I was just shocked. "What? He's the professor!" Eventually, I showed them my poetry, and then I joined their group at SF State and started getting active and fighting for the inclusion of women and people of color in creative writing and other classes at SF State. I got active, and I joined the creative writing caucus. That's how I got started. I'm glad I mentioned it to my fellow students in the feminist studies classes. A couple of them were social feminists, and that's also how I met the Freedom Socialist Party and Radical Women at that time.

Your work at Bethlehem Steel, of course, makes it into your poetry. Tell me about how those things came together.

It started with my late friend and comrade, Karen [Brodine]. She's one of the women I met in my feminist studies classes. We did a workshop in the creative writing caucus, and she said to me, “You have to write about work.” I asked, “Why? I'm only a secretary.” "Nellie,” she insisted, “You have to write about work." That started it.

I found I had a lot of stories, and the poems started to come out, poems I didn't know were there. I think some of my best pieces are related to my life as a worker, as a woman worker, and being Chinese and a woman of color. Because there was so much racism and sexism that I encountered throughout my whole working life. What was really exciting is that there were all these possibilities opening up for becoming a writer, becoming a poet, that I didn't know [were available to me].

And then how did you get involved with Radical Women and the Freedom Socialist Party?

Well, that was Karen [Brodine] and another person, Sukey [Wolf]—they were in my feminist studies courses. We got to know each other through the creative writing caucus, and we had started organizing. They were recruiting me, but I didn't know that at the time. I started reading Marx and Engels, and I was invited to go to a meeting that the Freedom Socialist Party and Radical Women, their sister organization, were organizing. On the agenda, I remember, was the subject of divorce. I thought, "What in the hell does that have to do with the left and politics, and such?" That really got me going, thinking about it. Because I was divorced-- no, I wasn't yet, I was still married.

That was really kind of a kick in the butt to me, and I started understanding and reading more. The reading, the writing, and the activism all started to come together where again, my consciousness—I realized I didn't know a lot of stuff. That is how that all came about, and I began to look at my life as a working person. A lot of what I wrote, I wasn't really aware of what was coming out. I just wrote what I was going through. Do you know my poem, “Toss Up”?

You call meinto the hall. Standard procedurefor a conference.

You ask me:

if we had a fight, whose side would you be on?

His because he is Chinese, or mine because I am a woman?

That came from an actual experience with a supervisor who said that to me. Of course, that's one poem that I’ve memorized because it's short enough.

Actually, it was several years before I decided that that's what I wanted to do: to be an activist. All the ideas of socialism, Marxism, and the ideas of feminism—all those were a part of entering my body and my brain. That's what happened.

The topic [of the meeting] also had focused on the late Clara Fraser. She started the Freedom Socialist Party along with some others, when the party broke away from the Socialist Workers Party. Some of the issues were on feminism, on China, on the woman question, as we talk about it in socialist politics. That became a real draw for me and really excited me. I thought, “Maybe I shouldn't just be writing about family, being Chinese American, and being a working woman, et cetera.” That all started to enter into my life with what I wanted to do as a writer. Although I still have never really said, "Oh, you're a writer. You're a poet.” I always think about, "If I say all those things, then there would be too many expectations for me to fulfill those ideas or positions." That's when I began.

When I joined the Freedom Social Party, I was just really thinking about how I could contribute to making change, and what kind of a society we live in when we have racism, sexism, and class oppression. It all started to gel for me as a place where I wanted to be and where I wanted to work.

Now, as an older or a more mature person, [chuckles] hopefully, there was more to poetry than just expressing myself. There was a connection to other people of color, to women, to family, whether chosen or not. Those kinds of issues all came up for me. I would say that was what really kicked everything off. Then, of course, my husband was very angry that I was becoming radicalized and socialized, though he appreciated my publishing and getting a few poems out.

What were some things you were reading or encountering at that time that motivated you to embrace socialism and feminism?

It was really looking at the conditions of women. Radical Women is an organization that still exists and is a sister organization of the FSP. Reading The Radical Women Manifesto was very instrumental in helping me to think more and to understand historical materialism. I began to learn how these concepts connected to my own life, the life of my communities from which I have come.

Since I was a feminist, I thought I was unusual, because in the classes at SF State, there weren’t a lot of people of color or women of color. I got very excited when an instructor in Women's Studies introduced a new anthology that came out that had the writings of women of color. Many of them were radical women of color, some of them were lesbian. But there was all this social and political context in their works.

I was very excited and at that time, I still saw myself as a beginning poet and writer. But I still thought, "How come I'm not in that book?" [laughs] I just didn't know why that seemed really important to me, but I also was looking for stories, poetry, and essays on people of color, women, and feminism.

When I began to read a lot of these books and booklets on feminism and socialism, it really began to make sense to me. I'm just not living and growing up as a personal person. [chuckles] I began to develop an understanding of dialectical materialism and how it relates to me and what I was doing. I began to understand all these wars, like what World War II was about, or what happened in the Vietnam War, which got me thinking about the social and political aspects of life that were connected to the personal. Why did I always think that my life was my life, and if something didn't happen, it was my fault? Or if something did happen, I'm somehow responsible? I wasn’t understanding those connections, living as a human being.

One of my experiences as I was beginning to learn through books and activism—there was a bookstore in San Francisco's Chinatown or Manilatown area. I think it was called China Books. I was so curious, I used to go in there and start looking at books. I started talking with one of the owners, and I was interested in what happened with China, because my parents were from China. The China they came from was a small village in Guangzhou or in Canton. I was totally curious and interested, so I began to go to that store and pick up some books.

At that time, I didn't understand what Maoism was, I didn't understand Trotskyism or Stalinism. Freedom Socialist Party also had a lot of documents and books and publications that I began to read and absorb. But I think the key was feminism. That drew me to the Freedom Socialist Party and Radical Women. We were all women who are a little bit older. Not in their late teens or early 20s, but in their 30s and 40s and up. That was something that drew us together, as well as ethnic studies, or women's studies, or LGBTQ [issues] and labor and such.

I already mentioned that Karen encouraged me to write about work. That was another opening when I began to see. I didn't know what class was at all and so those were part of what I see as my stepping stones into joining and being active. I changed personally, and it was because of the political that I was able to read, understand, examine, analyze, and question everything.

You were most active with FSP in the '80s and '90s. Looking back at those years, a lot of people would characterize them as counter-revolutionary or reactionary times after the Civil Rights Movement. What were some of the struggles you and FSP faced?

For me, I love what we were able to do. It's not like everything is a victory, because it's not easy being a revolutionary feminist, let alone a revolutionary feminist of color. [chuckles] Not to mention being a little older. Because you're going against the current. If I keep on writing and if something gets produced or published, that's of course not the end-all be-all.

But I also see writing as activism. What kind of a country do we really have? Is this the kind of United States that we really want to build? I want to be a part of that change if I can. My work is related so much to seeing the possibilities of a changing world, that we need to build for a society that does not chase after profits or money for military and arms manufacturers.

The whole concept of leadership is a part of what we work on and think about. What is a leader and who is the leader? I can't explain it all in our interview, but leadership is a relationship. Leadership comes with what we think we can do, and the vision that we have for building a society that would eliminate so many of the things if money, profits, and domination weren’t a priority.

I've also been baited for being a red or sticking with the FSP. One time, a friend of mine told me, “Clara Fraser is a racist." I said, "What?" This friend of mine, she was a co-worker at the time, and I said, "You think I would join a movement or an organization that was racist?" She couldn't answer me, and I thought, "Now why would she think Clara was a racist?"

She obviously didn't know the work of Clara Fraser, who's a Jew, whose parents were socialists and union organizers. There are a lot of battles we have to fight, just because we're of the left. Other times when people say, "Oh, you shouldn't join that organization," or, “you should stay away from those women because of what they're doing." I would say, "you know what? I'm one of them."

Then the conversation doesn't go further, because of a lack of time or whatever the circumstances are. Or there's little respect you have of me, because I'm doing something different from what you're doing and what you're thinking. It's about being open, if you can be, to the ideas, to the vision, to the work, and to our global reality.

Even on the left, among socialist groups, we have a lot of differences. But as Trotskyists, we talk about the need for a united front, where we can join and work together. We can raise our own banners, but we have to understand that we share a goal of what we want this movement to be. What are our possibilities, when the neo-fascists come riding into town, or the anti-abortionists come into San Francisco every January? Usually, those who are protesting are small in numbers. There's also a larger question of how the left has to organize. So that's part of what I'm trying to do as a member and activist within the FSP.

I want to go through some of your friendships and collaborations with other Asian American poets as well. We can start with Merle Woo. How did you meet Merle?

Well, I was going to SF State at the time, and I was in a class. Then I had a friend in the class who was taking Merle's class. She was teaching at SF State, and I didn't know her. Because I was only going to school at night, I said, "Oh, I can't take it.” But she was doing a class on Asian American women. I said to my friend Mimi, "Why don't you find out from Merle Woo if I could talk with her or meet her? Because I can't take the class."

Well, then she brought back a tiny piece of paper, and it had Merle's phone number on it. I called her, and that's what started our friendship and we started collaborating a lot. Then I was in the Women's Caucus in Creative Writing at that time, which became the Women Writers Union at SF State. I introduced her to the caucus, and she met Karen and we all started to do stuff together.

The first time I met Merle was at a reading for my first book. It was Dreams in Harrison Railroad Park. She came with a fellow teacher of hers. I think she also brought her son, Paul, who was only 11. Anyway, we met and that's when I met her. That's how we started our friendship. Then I introduced her to what became the Women Writers’ Union, and she joined it.

We were two women of color, two Asian American women that were the only—No, there was a Black woman. There was a Black woman also involved, but all the other women were white. Many were lesbians, and Merle is a lesbian. It was just fascinating, the encouragement and the push came from women who were radical and women who were gay.

You've also collaborated a lot with Mitsuye Yamada.

Have you seen the film, Mitsuye and Nellie, Asian American Poets?

Yes, I have.

Oh, good. I'm glad you saw it. That's also connected to SF State. Allie Light [the director] was a teacher. Allie is actually a neighbor of mine. She lives right here in Glen Park. She and her husband [Irving Saraf] were filmmakers. Allie was teaching a class called the Woman as Creative Agent. When I saw the class, I said, "I'm signing up for that." She and this other woman taught the class. That was one of the most exciting things I've ever gone through. We learned to write in dream journals and such…

Allie knew Mitsu. I didn't know Mitsu at that time. I had heard of her, but I didn't really know her. I knew what she had written, and I had gotten her book, Camp Notes. To cut to the chase, Allie talked to both Mitsu and me, and she said, "I'm going to make a film, and I want you guys to be in it." She knew us older Asian American women who were poets and who were feminists. What pushed her towards that was that there was a film festival going on in SF State, and there were films on Black women and white women, but none on Latinos or Latinx, nor on Asian American women. She evidently got the bug from that. I thought, "Okay, I'm going to be in a movie." [laughs]

She didn't really write a script, but she submitted an application for the National Endowment for the Arts. Even before she got the grant, she started filming us. I was living with my then-husband in Oakland in a Victorian that his grandfather built. She started filming me there. That's how the film got started. Then she got the grant, then we went to--which camp was it? Because of Mitsuye’s experiences from the concentration camp when the Japanese Americans were sent to the camps after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

What do you remember about the very first time meeting Mitsuye?

Our filming experience together, and the fact that I really liked what she did in her writing—I think that there was that connection. She and her brother, Mike [Yasutake], in particular who was a priest—they were activists and supporting political prisoners, particularly the African American men who were imprisoned. I was getting another opening to what was going on with people of color, and that was all through Mitsu. You know, she's 99 now, I just received a Christmas note from her. We talk now and then, usually through email or a text, but we still have that connection. The filming really brought us together so much closer.

And how did you meet Kitty Tsui?

We formed Unbound Feet, which consisted of Kitty, Canyon Sam, Merle Woo, Nancy Hom, me, Genny Lim. I never knew who started it exactly, but I think we found each other through the community, the movements, and feminism was a strong part of that. We were together for about a year and a half, two years. It wasn't very long, from the late '70s to the early '80s.

What did you do together?

We wrote, and then we shared our writings. We didn't do workshops—well, maybe we did with each other. Then we said, “We have to read this to the community, we want to read our work.” Nancy Hom did this poster, and we did a performance. She's a great graphic artist, a community artist, so this is how we started. That's how I met Kitty and then I got to know Nancy, and that's when I really got to know Genny, Merle, and Canyon as well.

Do you know of a poet by the name of Stella Nanying Wong? She was a little older. She was very well known in the Chinese American community. When we started though, she wasn't a part of the group. We actually started with Stella, but we weren't Unbound Feet yet. We were just getting together to share our writings and to perform.

Most of us in Unbound Feet were either Cantonese-speaking or Taishanese-speaking. I’m part of the Last Hoisan Poets, with Genny and my sister Flo. Kitty is Cantonese, she's not Hoisan speaking. Her background is really fascinating. Her grandmother was an opera star. I think she even said that her grandmother was a lesbian, because they never really talked about it. That was just really fascinating. Anyways, that's how Kitty and I worked together for a couple years.

In 1983, you went on a trip to China, the US Women Writers Tour to China. It was right around the time where China was reopening again—

Yes, because China reopened after Nixon in the ‘70s. You want to hear about how I got into that? Sometimes it's just by chance and by luck.

I knew Tillie Olsen. I think she liked my writing and knew of me, although I didn't really know her well. One day, she called me up. I was already divorced then, and I was living alone. She called me and said, “Nellie, there's going to be a trip to China with the US-China Peoples Friendship Association, and there are no Asian American or Chinese American women on this trip. Can you come?”

The trip was in 1983, so in 1982, I was still working at Bethlehem Steel. However, we had already been notified that Bethlehem Steel was shutting down. I knew I would be out of a job at the end of December. When Tillie sent that, my first book was out, and that's all I had. I used my severance pay to finance my trip.

That's what happened there. I was delighted that Tillie called and asked me to go. I said, “Wow, I'll try to go to my father's village,” which I did. [laughs] By luck, I got to go to my dad's village in Guangzhou. It was in the Taishan area around the Pearl River Delta. Our village was the Taishan-speaking village.

What was that like for you, visiting your dad's village?

It was really exciting. We met members of the Chinese Communist Party. We discussed feminism. The writers' tour had maybe a dozen of us or so. I was the only Chinese American on the tour, but there was also an Indian American poet. The rest were white women, both gay and straight. It was mixed. Alice Walker was a part of that, so was Tillie. And I roomed with Tillie.

Tillie and I got to know each other more. Also, she had invited me one time to meet Ding Ling, the very, very prolific, well-known woman writer of China, a novelist. I was supposed to meet Ding Ling in San Francisco, when she visited the United States. But Tillie gave me the wrong date. [laughs] I didn't get to meet her. But on this trip, I got to meet her, finally!

Her translated writings inspired me, even though I’m US-born, just in learning more about the feminist women in the movements here and in academia who were publishing her stuff.

Today you're part of another poetry collective, the Last Hoisan Poets. How did that come about?

That got started, Joe, because we were writing using hoisan-wa in our poetry and other writings. Flo, Genny, and I were reading at the Chinese Historical Society one time a few years ago. However, I got sick and I couldn't go. Flo and Jenny did it, and they both didn't know that their poems had these Hoisan phrases. They clicked on that. Then another time, we were going to do a reading and then this time I wasn't sick. We came up with the name, Last Hoisan Poets. We're not the last, but we just thought it was a good thing to name ourselves.

We presented at different places, like the Chinese Historical Society and elsewhere, as well as a couple of events at the de Young Museum, where we did a tribute to Hung Liu. She was a well-known Chinese artist, and her background was just fascinating. She came to the United States in the ‘80s. She taught at Mills College, and her paintings are just monumental. She became very well known. Flo knew her and I met her, but Flo knew her well. Just recently, we also did a tribute to the African American artist, Faith Ringgold. We would write poems, especially around their lives and their art, and then we also then include Hoisan phrases.

I've written some poems entirely in Hoisan. I would write it, and I would sound it out phonetically. When I was younger, I thought, "Oh, we don't need to speak the dialect, we're Americans.” But I started to write at night, after I lost the jade heart my mother gave me when I was moving. I'm really mad for having lost that. My mother was already gone, so I decided to tell her [in writing], but what I told her came out in the Hoisan dialect, because that's what we spoke when we were kids.

What are you reading these days? Do you keep up with much contemporary poetry?

I don't buy every book that's come out, but I think I'm very, very interested in novels and other writings. I read a lot of poetry, but some of the poets that really stick with me have been people like Mahmoud Darwish, a Palestinian poet. I have about a dozen books of his that have been translated into English.

Well, some of the recent books I've read—I really love Min Jin Lee, Pachinko. I've read that two or three times. Did you watch the series on Apple?

No, I don't have Apple TV.

I thought they did a good job. I have read the book several times, and it doesn't do exactly what the book does. It never does, but it's well done.

There are some very well-known Korean actors in the series.

Yes. I'm also a nut on Korean drama. Taiwanese, too. I don't watch Japanese dramas so much, but I'm a huge fan and student of Japanese cinema. I love [Yasujirō] Ozu, [Mikio] Nakuse, and Kenji Mizoguchi. I love film and I watch a lot of international films, but I'm a huge fan of Korean and Chinese dramas.

Do you have any favorite dramas?

Well, Winter Begonia is one I just watched, and it's about the Peking Opera. Winter Begonia might be 40-something episodes. Winter Begonia is just terrific. There are others I like, but I think I'll take up too much time talking about it. [chuckles]

Well, those are all my questions. Nellie, thank you so much for your time today. It was wonderful being in conversation with you.

Joe Wei is an assistant professor of English at the University of Georgia. He's currently working on his first book, Asian American Literary Organizing, 1970s to the Present, which investigates the role of Asian American literary organizations—from Kearny Street Workshop to Kundiman—in realizing and sustaining models of literary production outside of mainstream literary institutions.

Dear friends,

I am happy to announce the Winter 2026 courses at Asian American Literary Archive, Reading the Romance in Asian American Literature with Kathleen Escharcha and Asian American Studies for Right Now: The Great Teach-in, with Poems with lawrence-minh bùi davis and Mimi Khúc.

Reading the Asian American Romance

Instructor(s): Kathleen Escarcha

Term: Winter 2026

Dates: February 3, 2026–February 26, 2026 (8 sessions)

Times: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 8:30–9:30 P.M. ET / 5:30-6:30 P.M. PT (1 hour twice a week)

Enrollment: 15 students

Enrollment Closes: February 2, 2026, 11:59 P.M. ET

While many classes on romance fiction begin with British Romanticism, this course turns to twentieth-century and contemporary Asian American and transpacific texts to foreground a different set of concerns: restrictive immigration and anti-miscegenation laws, Orientalism, queerness, and imperialism. We will examine how race, migration, and empire shape the (im)possibility of love, marriage, and family formation for Asian and Asian American communities. Pairing literary fiction and film with cultural history and critical theory, we will explore how writers use romance to interrogate compulsory heterosexuality, immigration policy, and nation-building. Readings span North America, the Philippines, Japan, and Trinidad, situating Asian American literature within global circuits of empire and migration while rethinking what and whom the romance genre has historically excluded.

Asian American Studies for Right Now: The Great Teach-in, with Poems

Instructor(s): lawrence-minh bùi davis and (proudly lazy TA) Mimi Khúc

Term: Winter 2026

Dates: January 15, 2026–March 19, 2026 (10 sessions)

Times: Thursdays, 7:30–8:45 P.M. ET / 4:30-5:45 P.M. PT (1 hour 15 minutes once a week)

Enrollment: 100 students

Enrollment Closes: January 14, 2026, 11:59 P.M. ET

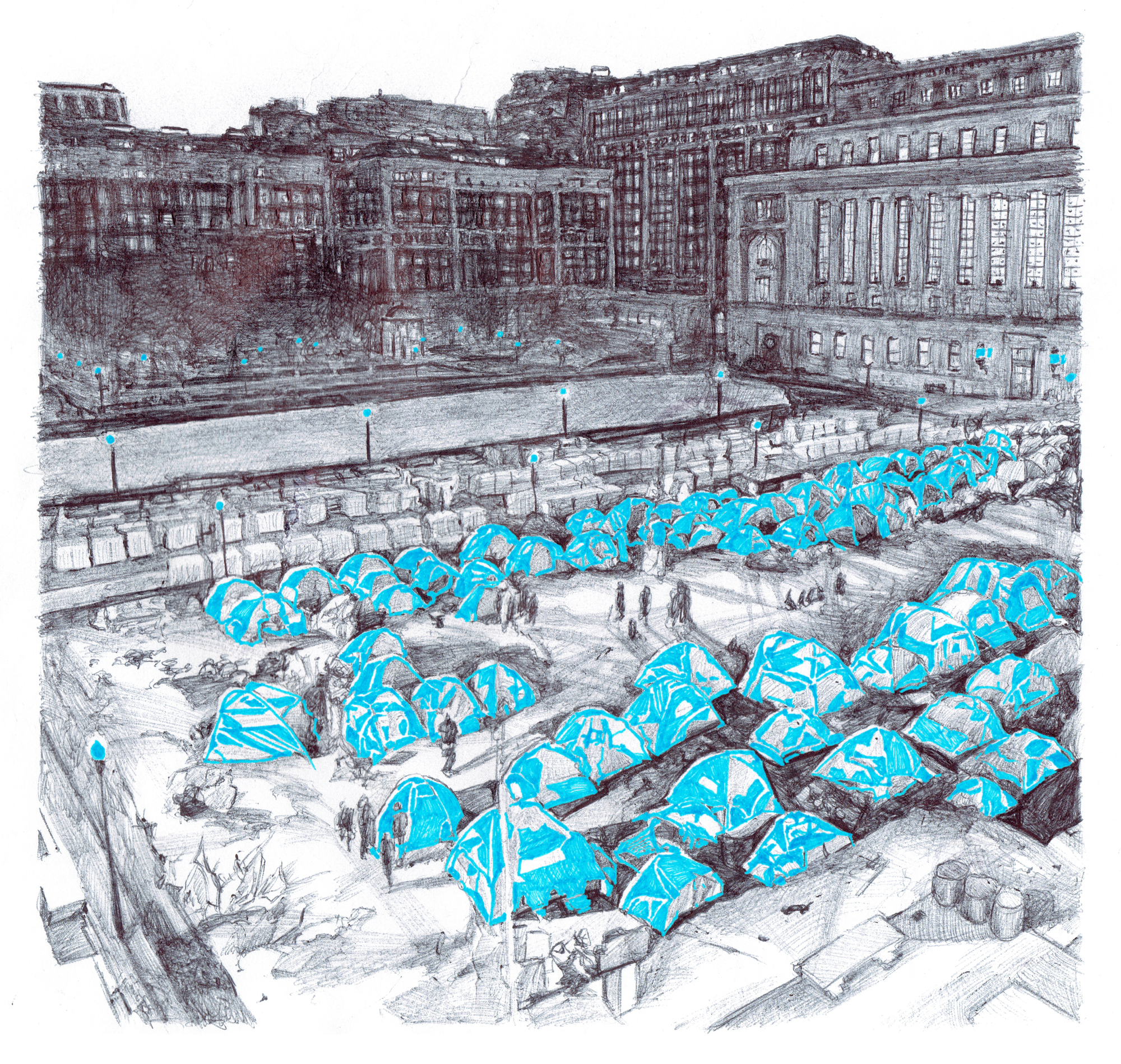

An Asian American studies teach-in for the crumbling sinkhole of 2026 America. With poems. Join lifelong Asian Americanist scholars learning with and from students new to the field alongside leading Asian American poets and writers. Together we’ll weigh the possibilities–and responsibilities–of Asian American studies and Asian American arts right now. With sessions on genocide in Gaza; the sweeping purges of all things DEI and QTNB; the abyss of the Asian American mental health crisis; the radical potentials of friendship and grief. Throughout will be a commitment to DIY access culture and disability justice we'll wear like garbage bags into a monsoon. Course texts will include “hijacked” poems by George Abraham; a class-sourced FAQ on dealing with EYE-CE; an “intimate lecture” by newly minted US Poet Laureate Arthur Sze; queer eco-justice stickers and film shorts by Jess X. Snow; the spring 2024 student encampments as epic poems. Course learning objectives will include fun, vulnerability, trust-building, lip-biting hope, and–cue grandiose music–the groaning sounds of doors opening inside us.

Asian American Studies for Right Now was first taught by Ida Yalzadeh in the summer of 2024, teaching foundations of Asian American studies while also directly addressing topics such as anti-Blackness and Palestine. When I asked lawrence to propose a course for this Winter 2026 session, his idea for The Great Teach-In seemed directly aligned with the ethos of Ida's initial course.

Back then, when the goal was just to get Asian American studies to the public, the course seemed out-of-the-box, but now, as critical race theory is being targeted in the academy and books continue to be censored, it seems more to me as the beginning of something new. I aim to continue Ida's idea at the Asian American Literary Archive as the cornerstone of our educational offering: a foundations in Asian American Studies course that is also an un-institutional space of experimentation and connection that addresses the history we are living right now.

To that end, Asian American Studies for Right Now: The Great Teach-In, with Poems, will follow a different format than our usual seminars. The course will be delivered by lawrence and Mimi with a variety of guests, and serves to be as much an educational space as an activating space—for archives and beyond.

The Archive is also moving beyond classes. Last month, we launched Box 68, an archive of interviews with movers and thinkers in Asian American literature. Over the next few months, look out for new interviews with poet Nellie Wong, scholar Keva X. Bui, and preservationist Sine Hwang Jensen.

I am grateful to be in community with you all.

Best,

Yanyi

Director, Asian American Literary Archive

About This Course

Course Info

Instructor(s): Kathleen Escarcha

Term: Winter 2026

Dates: February 3, 2026–February 26, 2026 (8 sessions)

Times: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 8:30–9:30 P.M. ET / 5:30-6:30 P.M. PT (1 hour twice a week)

Enrollment: 15 students

Enrollment Closes: February 2, 2026, 11:59 P.M. ET

Description

While many classes on romance fiction begin with British Romanticism, this course turns to twentieth-century and contemporary Asian American and transpacific texts to foreground a different set of concerns: restrictive immigration and anti-miscegenation laws, Orientalism, queerness, and imperialism. We will examine how race, migration, and empire shape the (im)possibility of love, marriage, and family formation for Asian and Asian American communities. Pairing literary fiction and film with cultural history and critical theory, we will explore how writers use romance to interrogate compulsory heterosexuality, immigration policy, and nation-building. Readings span North America, the Philippines, Japan, and Trinidad, situating Asian American literature within global circuits of empire and migration while rethinking what and whom the romance genre has historically excluded.

Platforms

Google Drive: Participants will receive all readings over Google Drive.

Zoom: All class sessions will be held and recorded on Zoom until 1 month after the course's end.

Class Cap & Enrollment

The class has a capacity of 15 students. 2 full scholarships are available to folks where paying the enrollment fee is a financial burden.

If you are interested in a scholarship, please fill out this short scholarship form. Scholarship applications are due by January 19 and participants will be notified by January 26.

Who Is This For?

All with an interest are welcome!

About the Instructor(s)

Kathleen Escarcha is a Ph.D. candidate in English at the University of Washington, where she teaches courses in composition, ethnic studies, and multiethnic literature. Her research examines how Filipinx and Southeast Asian Anglophone writers use fiction to explore how gender mediates the entanglements of empire, authoritarianism, and modernity. She also serves on the board of the Association for Asian American Studies.

Price

$349 USD

Enrollment for this course is now closed.

About This Course

Course Info

Instructor(s): lawrence-minh bùi davis and (proudly lazy TA) Mimi Khúc

Term: Winter 2026

Dates: January 15, 2026–March 19, 2026 (10 sessions)

Times: Thursdays, 7:30–8:45 P.M. ET / 4:30-5:45 P.M. PT (1 hour 15 minutes once a week)

Enrollment: 100 students

Enrollment Closes: January 14, 2026, 11:59 P.M. ET

Description

An Asian American studies teach-in for the crumbling sinkhole of 2026 America. With poems. Join lifelong Asian Americanist scholars learning with and from students new to the field alongside leading Asian American poets and writers. Together we’ll weigh the possibilities–and responsibilities–of Asian American studies and Asian American arts right now. With sessions on genocide in Gaza; the sweeping purges of all things DEI and QTNB; the abyss of the Asian American mental health crisis; the radical potentials of friendship and grief. Throughout will be a commitment to DIY access culture and disability justice we'll wear like garbage bags into a monsoon. Course texts will include “hijacked” poems by George Abraham; a class-sourced FAQ on dealing with EYE-CE; an “intimate lecture” by newly minted US Poet Laureate Arthur Sze; queer eco-justice stickers and film shorts by Jess X. Snow; the spring 2024 student encampments as epic poems. Course learning objectives will include fun, vulnerability, trust-building, lip-biting hope, and–cue grandiose music–the groaning sounds of doors opening inside us.

Platforms

Google Drive: Participants will receive all readings over Google Drive.

Zoom: All class sessions will be held and recorded on Zoom until 1 month after the course's end.

Class Cap & Enrollment

The class has a capacity of 100 students. 10 full scholarships are available to folks where paying the enrollment fee is a financial burden.

If you are interested in a scholarship, please fill out this short scholarship form. Scholarship applications are due by December 22 and participants will be notified by December 29.

Who Is This For?

All with an interest are welcome!

About the Instructor(s)

lawrence-minh bùi davis, PhD is a refugee diaspore, curator, writer, and troublemaker who lives as a guest on the ancestral lands of the Piscataway Nation. A co-founder of the arts anti-profit AALR (2009), the Asian American Literature Festival (2017), and the Center for Refugee Poetics (2018), he believes in stewardship of literature as social and ethical ecosystem. As far as anyone knows, he was the first curator of viet descent at the World’s Largest Museum and Research Complex, as well as the first to be exiled from it. Sometimes you can see new things by the light of his neurodivergence.

Mimi Khúc, PhD, is a writer, scholar, and teacher of things unwell. Her work includes Open in Emergency, a hybrid book-arts project revolutionizing Asian American mental health, and the Asian American Tarot, a reimagined deck of tarot cards. Her creative-critical, genre-bending book dear elia: Letters from the Asian American Abyss (Duke UP, 2024), is a journey into the depths of Asian American unwellness at the intersections of ableism, model minoritization, and the university, and an exploration of new approaches to building collective care.

L + M are partners in teaching, artmaking, and life. Both are Scorpios, and, you know, Scorpios sharpen Scorpios.

Price

$349 USD

Enrollment is now closed.

Since 2022, the Asian American Literary Archive has been offering courses in Asian American studies and literature to the public. What started as an experiment and proof-of-concept has leapt into ongoing opportunities for working adults to access not only information but expertise around Asian American issues and art. I look forward to announcing an exciting slate of offerings for Winter 2026 in the next few weeks.

However, the intention was never to stop at courses. This is an archive, after all. Naively, I first thought that I could scan some ephemera, put it up on a website, and call it a day. Copyright issues came up immediately and I had to give up the idea of scanning and sharing (and yes, if you’re an archivist who wants to give me advice on all this, I would love to chat).

With the same naïveté, I pivoted those grand plans to a literary journal instead. On this end, the limitations of time, money, and, in the case of out-of-print works, copyright, came into play. I wanted to pay the contributors and the staff even at nominal fees. Given these limitations, after discussing it with assistant editor Winona Guo, it just didn’t align yet to build a magazine that had no budget.

When I was recovering from top surgery, I read interviews with artists voraciously in The Paris Review. I was hungry for artists’ intentions behind their own work; tidbits of who they were as people and also how they found a way to write in their moments in history. Outside of the literary world, I read interviews with academics to better understand their theories and, again, to understand who they were as people, not just theorists. Soon, Winona and I landed on interviews as a genre especially aligned with the Archive’s purpose as a community gateway to Asian American literature.

Introducing Box 68: Interviews in Asian American studies and literature

Box 68 is so named for the year in which the term “Asian American” was coined, the activist movements it came out of, and the boxes of materials one requests from archival collections.

In its first iteration, as a newsletter and archive of interviews with scholars, preservationists, Box 68 will be delivered as special editions of the Asian American Literary Archive newsletter, which you are already subscribed to if you received this directly.

To that end, I am excited to announce that you can read the inaugural interviews right now!

I’m always searching for something, for something larger where there’s no answer, no solution. No one’s even going to talk back to me. There’s no response. It’s literally the void. But I am searching. It’s metaphysical, philosophical, it’s something bigger.

—Poet Victoria Chang on With My Back to the World

I didn't notice the usage of the phrase until you pointed that out. I was thinking about how some of this work, labor intensive work, whether it's from activists on ground or activist storytellers—has a method of messiness. All of that is happening simultaneously, at the same time, because often when we are trying to understand politics—and I mean the ideological work that we do, inside or outside the university—we often are unable to reconcile with contradictions. Certain people think as if politics needs to be pure. Just because one person is supporting one cause, they also have to support, you know, the other X, Y, Z.

—Scholar Rajorshi Das on Messy Trans and Queer Storytelling

Over the fall/winter season, we be publishing the rest of our initial interviews with archivist and librarian Sine Hwang Jensen, scholar Keva X. Bui, and poet Nellie Wong.

Like with all new things at Asian American Literary Archive, Box 68 is an experiment I intend to grow for sustainable longevity. This marks the first leap for the Archive beyond courses since its inception, and I’m really excited to see what possibilities and connections can come from it in the years ahead.

In solidarity,

Yanyi

Director, Asian American Literary Archive

Victoria Chang and I met on a blustery morning in Kansas City between the panels, stop-and-chats, and barbecue of AWP in February 2024. We started off our conversation not face-to-face but over text message: I’m here, she was saying, but as I scoured the rows and tables of customers in the coffeeshop, no Chang appeared in the corners of the coffeeshop at which I had just arrived.

It turned out that we had gone to different locations of the same coffeeshop, as tourists are wont to do over local chains. There we were, I think now, two poets living out the meaning of ambiguity. A ride hail later, I stumbled into another coffeeshop of the same name, but this time Chang was sitting in a corner reading a book of poems next to an enormous and beautiful elephant ear plant.

Over the next hour and a half, we touched on the making of Chang’s then-new book, With My Back to the World (FSG 2024), her conversations with the art and writings of one of our mutual loves, Agnes Martin, her search with and for art, and her mental health journey through a series of experiences with death and anti-Asian racism on personal and political levels.

Victoria Chang’s most recent book of poems is With My Back to the World, published in 2024 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in the U.S. and Corsair/Little Brown in the U.K. It received the Forward Prize in Poetry for Best Collection. A few of her other books include The Trees Witness Everything, OBIT, and Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief. She has written several children’s books as well. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Chowdhury International Prize in Literature, and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship. She is the Bourne Chair in Poetry at Georgia Tech and Director of Poetry@Tech.

How did you end up with such a different career path?

I think I’m just interested in a lot of things. Poetry has always been around, but so have other things. This is what ended up being a larger part of my life than maybe I had originally planned.

Like a happy accident.

Well, is it a happy accident or is it just an accident? I just accept it. Whatever path happens to me, I just take it and that mindset is why my background is so varied. I just go with the flow and sit on a little boat in this river and just go along wherever the river takes me. It truly is what brings me joy about being alive.

How did you come to those interests that have pulled you across disciplines and genres?

I’m always searching for something, for something larger where there’s no answer, no solution. No one’s even going to talk back to me. There’s no response. It’s literally the void. But I am searching. It’s metaphysical, philosophical, it’s something bigger. My parents became ill when I was in my thirties and they both had long illnesses so I became very consumed with death, even more than before. I had to do a lot of caretaking and witnessed some pretty terrible things. It opened up what was already in me, this seed of thinking about death, what happens after, what are we going to do with the time while we’re here, and what matters.

What is the universe of this search for you?

It’s about perception. When I see something, I know that that’s the thing, or the thing adjacent. If I meet someone, I know that person is in the same space that I’m in. When I meet the real thing, whatever the real thing is for me, I know. It’s like that Tadao Ando chapel, The Church of the Light in Osaka, or when I walked into the Ellsworth Kelly chapel in Austin. I know this is the thing that I’m looking for. When I meet someone who’s trying to grapple with those same big questions, I just know it: this is my person. I love reading, because reading is a way to meet the people who thought or are thinking about these questions.

It's a way to travel.

You can read a poet you love, you can feel it in your body. That’s why I also love going to museums or looking at things and just walking around because I feel this kind of awe. It’s never manufactured. It seizes you at the moment. When something seizes you, you go toward it and walk toward it. I think the job choices and the life choices I’ve made have tended to be like that. Not to say that I haven’t made mistakes or gone in the wrong direction, but I just kind of follow my instincts.

Because With My Back to the World is so much of you really looking at these paintings, drawings, and prints that Martin did, I’m curious about how you approach an object when you see it. Did you devise something particularly for this, or was it part of your everyday practice?

I started with a poem that the MoMA commissioned. The catalog was too large. And I just sat quietly and Agnes Martin came to me. I had read her writing a long time ago—Brian Teare had written this gorgeous book—I was familiar with the artwork and had read all the writings. I didn’t have this visceral reaction to the artwork back then. But then, much later, when I was writing the Agnes Martin poems, I think I was depressed. It was a combination of my mother having passed away and all the stress of caretaking for her and losing her. It was the stress of my father still being around and having so many problems.

Having my own experiences with her work too, I feel like Agnes Martin is the perfect artist to be with in that depression.

Suddenly her work resonated with me. I felt it—I felt the lines in my body. I felt everything. Now, in retrospect, when I look back at the time, I also had bodily and chemical changes due to menopause too. I think I gained thirty pounds without even realizing it. I didn’t have anyone to talk to about it and I didn’t even know. Sometimes you don’t know because the idea isn’t even in your sphere. I just didn’t understand. And the Asian American murders that occurred in Atlanta, the spa shootings, it’s very traumatic. For all of us. There’s so much of that anti-Asian hate that was just so triggering, because it’s what I had experienced while growing up in Michigan.

Proof of the thing that you've been afraid of your entire life.

Yes. And I grew up in the era of Vincent Chin in Detroit, Michigan. And I was bullied growing up. I was really afraid of all these things. It just worked its way into that first poem. After reading the poem aloud at a conference, I realized that I wasn’t done speaking to Agnes. Then I started looking at all of her pieces, reading everything I could find. And just engaging with her work and having a conversation. So the poems and doodles are a result of that. It’s just my conversation with Agnes Martin.

Martin thought of herself as an abstract expressionist, not a minimalist. I’m thinking of this with Dorothy Wang’s ideas around Asian American experimental poetry—it may not seem to be about race but has underlying links to it.

It’s funny that you mention Agnes Martin not being a minimalist because I just went over to the museum here and there was a minimalism section, and there she was. I thought that she would not be happy about that, being next to Donald Judd. The other thing I remember—I just wrote about this, I’ve been working on this weird prose thing—that I’ll mention too is that I’m actually very afraid to be seen. I hate being in public. I don’t like anyone looking at me. I’m happy to be anonymous.

The reception of my book OBIT, really surprised me. I don’t mind if people read my work. The books can do whatever they want. But I want to detach myself from the work, but it’s impossible to do so. So I’ve had to learn how to adjust. I hate having the spotlight on me. I don’t like that limelight at all. I’d never seek it. I did not ever anticipate or aspire for what happened to that book. And that actually made me have a lot of anxiety.

Given your history of having been bullied and also—

Which is also an embarrassing thing to talk about. Shame—

There’s lot of shame. But the hyper-visibility is also dangerous, right? Racially speaking, it’s like you’re standing on the corner with the lights on you, waiting.

Jane Wong and I actually talked about this in an interview with BOMB Magazine. We’re either hyper-invisible or hyper-visible, and neither thing is ideal because who wants to be invisible? You’re not even a person so why are you here? And then being hyper-visible, for me at least, is getting bullied—or getting criticized, or as you say, it’s dangerous. In my own house, growing up, if my parents were talking to me, it wasn’t to praise me.

If it’s silence, it means you’re good.

Exactly. If you’re invisible, you’re doing great. When you’re visible in your own house, it’s because I got in trouble. Or it’s because I didn’t do the things I was supposed to be doing. I was kind of lucky growing up because I was hyper-invisible for a long time because my sister had some issues that everyone was obsessing about. In school, I tried to be as physically small as possible. I didn’t say a word. Even in college classes I hardly said anything. I was really quiet all growing up. I think I didn’t understand that writing poems and putting them out in the world could actually expose you in ways that made me uncomfortable.

You also have been, at least in the last four books I can think of, you really have been moving through grief and death very publicly with very personal things. My family, for example, is like, please don’t write about us.

They don’t like it.

No, but then you also have to be, as Martin says, on your own vision. You have to be doing the work. You have to make choices about your personal relationships and the ways you exist on this plane in order to do that work.

We have to be true to ourselves and our own visions, whatever they might be or however organic they might appear. I didn’t want to write about my mother after she died. It just happened. And then my father couldn’t understand anything. His stroke was so debilitating, and his illness just kept on getting worse and worse.

That must have been really hard too.

But then it also meant I could write about him! He didn’t know.

Let’s talk about the work you’ve done for this book and in particular, depression. I saw you writing about it in different, refractory ways. The ocean shows up a lot, and water. Martin had a breakdown in New York in 1963 and did that painting Friendship for Lenore Tawney, which you wrote two poems on in the book—

When you just said that, Friendship, it gave me goosebumps. I love that piece. It’s so beautiful.

I mean, it’s gold leaf! But can you talk about the symbols in the book: the ocean, the horses, the grids?

When she had a breakdown, she just gave her paintbrushes away. I wrote about this in that I wonder who has her paintbrushes and who doesn’t know they have Agnes Martin’s blue from Night Sea underneath their paint brushes. That’s why I think I just borrowed her title With My Back to the World. It felt very appropriate for me because I had been so isolated. I just didn’t want to deal with the whole world anymore. Her action of moving and then traveling around and then having her own relationship with herself without all that noise of the art world. I connected with that so much. I’ve been hermiting myself for a long time now.

In terms of the symbols, I really found them while looking at each one of her pieces while I was writing. I acquired really nice plates that I could look at. One of the cool things has been running into Agnes Martin pieces in the world. I just ran into one here! It’s like seeing an old new friend. I think the reason why there are a lot of similar things happening between my poems and her pieces is that I was literally using her symbols and vocabulary to open up new spaces of thinking. Looking at her work really emptied my mind and refilled it. What was left were her lines. What was left were her colors. And there’s a lot of blue. A ton of blue. Light blue. Dark blue. I would say my two favorite pieces are the gold leaf one but also Night Sea that is at SFMOMA.

My phone background is Summer with the blue dots.

I love that! Night Sea, for example, is just that blue. When I’ve seen it in person, I was just in the blue. I was literally inside that blue. So these symbols of blue and water, whatever she allowed me to relate to, I just entered that space and riffed off of it. So it really is a conversation with her pieces.

Some of the poems started with just the number of lines. I was wondering if you went in and counted the lines?

I loved doing that. It was so meditative.

Like a rosary.

Yeah. And I’d screw up. I’d start wandering. I’d be like, where am I? Start over. 1, 2, 3, 4… And then other times I’d just count this way and count that way and multiply. It was like, No. Count them one by one. Do not do length by width and multiply it. Count them one by one. And then do it again. And do it again. Until you’re sure you got exactly the right number.

You were painting.

I feel like Agnes was writing.

Tell me more about that.

I feel like when people don’t like her grids, they’re actually looking at them as if they’re paintings. Like they’re the traditional idea of a painting. But when I started to feel as though I really understood her, I started thinking about her as writing. And also when I started thinking about not what was there, in the piece, but what wasn’t there. And what preceded it and what followed it. So it really gelled with my own thinking about poetry. What’s left on the page? It’s not the poem. And in thinking about Agnes Martin, I loved looking at all her math on notes and stuff. Three times twelve…She was calculating. To me, that is part of the work. The work itself is what punctures through. But it’s not the thing itself. I think a lot about how Agnes Martin’s pieces, for me, are about visibility of her process. You look closely, you can see the graphite marks, you can actually imagine her drawing. I think my poems are more about process too.

When you think about an ideal reader, or even yourself, when you return to it in ten years, how would you want to approach it?

I feel like readers are really important to the completion of a work, which is why I send my work out. If I didn’t believe that, I wouldn’t even send it out. I wouldn’t show it to anybody. But I actually do believe that it’s not truly complete until someone’s interacted with it.

I do feel as though when you read the book while looking at the paintings, it becomes so much more of a conversation. One thing that I admire about what you’ve done is the detail with which you interacted with the work. It feels like you are engaged in your own process of painting. Both of us have probably seen that documentary where she’s painting that red line—I think that is With My Back to the World (2003).

It is. And when that film opened up and it’s her…I started sobbing. I had an explosive emotion because I had never seen her. I purposefully waited to watch that. I didn’t want to see her interviewed, I didn’t want to see her talking, I just wanted to wait. But finally when I watched that, she was painting the horizontal bands vertically, and she was painting and talking, I had such a visceral reaction. I think this was also when I was emotionally in a tough space.

Why?

All the life things we were talking about. And I think I had already had such a strong connection to her work, and seeing her embodied like that, and seeing her work and seeing how those bands were made…It was like a spiritual reaction that I had that was very moving. Did you feel that way?

I think there’s an element of seeing someone embodied and knowing that they were a part of this world, and the tactility of you were here. As in, it’s possible for you to live and be alive in this world, so I can too.

Oh, yes! She’s very inspiring. I also liked how dogmatic she was in her writing sometimes. It makes me smile because people don’t always like people who have opinions, who live upon and just follow those things. It’s easy to not like those people, but she just laid it out there in writing. I really admire that. What she represents is solitude and living almost a Buddhist life. I think I can connect with that kind of asceticism and respect for the ineffable, the unknown, silence. All those things are very important to me.

I was curious about your own spiritual inclinations or leanings, and how you connect them with Martin in her own dogmas. There’s also an interesting layer here around the influence of East Asia and East Asian philosophies on that particular group of artists, not just painters, but also poets of that time.

I enjoy reading philosophy, art history, art criticism, poetry criticism—and then looking at Martin and reading all the criticism on Martin. My mother was quiet and anxious, scared, and a bit shy. She was interested in fortune-telling and fates, so when stuff happened to people—good things, bad things—she would always be like, that was their mìng 命 [fate]. When something happened to me, she’d be like, that is your 命. A fortune teller at my birth said I would have a really bad accident and when I got into a bike accident and almost died, my mother said, see? A split second difference and I would have died. I had maybe 50 stitches and lots of pain.

Chronic pain and probably PTSD?

Yes, definitely PTSD. Brain stuff happened.

Wait, how old were you?

Thirty…mid-thirties.

So this was also around all the other death stuff you dealing with.

About to deal with.

The accident must have changed your life.

I also started believing my mom. So I started actually not caring about anything.

Martin once said, You never leave your front step. And no matter how many steps that you take, you haven't actually moved.

Isn’t that glorious and freeing?

It is. It means that it is about presence. It feels like you’re doing your own dots in the grid with this book. The experience of the book is partly observing that and watching it happen. You know, also with the On Kawara sequences where you have a line or two from a particular day, which I’m guessing you were writing on a daily basis?

I was.

It feels like we’re in the moment, we’re in the waves.

On the Today poem, inspired by On Kawara’s Today series, I wondered what it would be like to write in real time? To have language meet the experience as close as it could be? So when my father was in his final hospice, where we had to make some tough decisions, I thought he was going to pass away in few days. Instead, he lasted almost a month. I wondered if we should start feeding him again? Did we make a mistake? Did the doctors make a mistake? I didn’t realize it was going to go on for so long. I thought I’d just write because he’d be dead in three days, or something like that. But he didn’t die. So what I ended up with is a long poem. I actually continued that project and I started writing prose.

But prose didn't end up in the book, right?

No, it’s a totally different thing.

I was curious about your artistic practice too. You said that they were doodles, but it looks like you have a visual art practice. How does the visual factor in for you?

It's a different way of entering the same space. Poetry is just one thing. It's not everything. It can feel like it's everything and it means a lot to me. I have a really special relationship with poetry. But it's just one thing in this world. Visual art is when you’re feeling like letters and language don’t feel right or enough. Then I’ll just move around and try different things.

I talked to my friend Rick Barot about this last year. We were talking about how I find the book as object to be extremely limiting from my own artistic practice. I think it would be neat to rip all the pages out in my books and toss them into the air, and publishing them into the sky. Why are we so wed to this physical thing? And why is everything at the left margin?

Would you ever do some kind of installation piece? I feel like in Dear Memory you were already doing work with photos and writings next to them, already working with mixed media and somewhat documentary forms. In your new project, you’re looking at the archives of others and their families, thinking about ethics of including them. And now you’re talking about just not wanting to be limited. Would you do something bigger?

Absolutely. And I always think don’t anyone needs to read my book, OBIT in one sitting. That book is long, all in the same shape. I’m needling the same material over and over again. It’s my own obsession. I imagine them to be taped on that wall here. In another city, hanging from a string somewhere or blown up on vellum that goes all over the floor. I sort of see them separated from each other, not all together. But there’s also a sort of beauty from that relentless grief that you get from that book that makes the book as object. But I’m also not sure that they’re meant to be all together. People in poetry can sometimes denigrate the project book or the series, and I don’t mind that at all. I always refer to the visual artists like Picasso’s blue period, Matisse’s cutouts, Calder’s mobiles, Neel’s portraits, and I could go on. I feel like that’s the space I’m operating in. I feel more a kinship with those kinds of artists. Agnes’s grids, then her bands later in life.

It sounds to me that repetitions of different kinds are important to you in your practice, and—

Obsessions.

In previous interviews, you’ve talked about how you wrote OBIT in two weeks. What was it for With My Back to the World. In some poems, your speaker observes the paintings in person. Did you actually do that?

Most of the visits were accidental. I never actually flew somewhere just to see them. I was invited to do readings in places and I love going to art museums and actually prefer that quiet to socializing. I just did that here Thursday night by myself. The museum was open until 9pm and it was lovely and quiet and I accidentally ran into an Agnes Martin piece.

The writing of that book took longer because it wasn’t just me writing from the inside out. It was me writing from the outside in. I really took my time. I’m so obsessive and I’m actually just a little too fast at everything. I do things too quickly because I get very excited. I read all the books on Agnes Martin so it just took longer. It was actually very good to slow me down. But I’d say it took me months to write this book, then I revised it, so maybe eight months total, which is fast.

I feel like you take breaks.

Of course! I have a life. I have things to do. Lots of things. Lots of people who rely on me.

Martin would take a year. Here’s the painting year, here’s the off year. She did that too.

Right. For me, it’s forced off-time.

Your work in this book is not only about your engagement with Martin and the beyond which I think is always there, but also this forced bodily witnessing of you witnessing—or your speaker witnessing—and also being particularly because of gender and race. Would talk about that and the gendered conditions, and labor, of your writing?

Speaking of gendered labor, I feel a great burden, gift, and responsibility for so many people I don’t know. I don’t know why I feel this way, but when I first started writing poetry, I was just looking for people to talk to or to give me advice or to help me. I had a really hard time finding those people. I think everyone does. Everyone just wants people to take care of them and help them. I was looking for people who look like me. There were very few of us at the time. We were very scattered. There was no internet. I feel like our community can sometimes be ungenerous to each other.

Yeah. And you’re from the Midwest.

Where are you from again?

Southern Illinois.

Okay, same area. We're constellated. We're not connected. And I think the way that we navigate this country, and in this literary world is like, there can be only one, and you're anointed by the white institutions. It creates this false competition. If you buy into that system, the system will imprison you. For me, I'm interested in connection, learning from each other, collaborating, horizontal work. Agnes Martin’s horizontal line. I feel like I need to do things that I would have liked other people to do. I feel like it's important to give back.

Yeah, it's creating the thing that you wish was there.

But it's a lot of pressure too. Because amazingly and excitingly, there are a lot of BIPOC poets, younger, emerging, older, that are just starting, and they all are looking for people who look like us. But it’s a lot of work. I'm willing to do that work as much as I can, because that is really important to me. I don’t know why I’m talking about that.

Well, I asked about the relationship between being Asian American and being a woman in the workplace. I think you talking about connection and making some of that visible in these poems is part of the actual process of being available. Being vulnerable about it.

And being honest and authentic. If people would criticize me, they would say, You're too blunt. That sort of bluntness is baked into our family culture. I definitely feel like some of the themes, looking back on it, were very feminist themes. I'm dealing with a lot of feminist ideas and feeling really oppressed by society. I felt like I had a container and whatever's happening in your life, you just throw it in there, and then blend it all up and see what happens to it. For me, the personal is a way to the universal, if there is such a thing. I think there are universal human emotions like sadness and happiness, but to reach those things through the personal is so odd, but I think that's actually how you connect with people is by being yourself and being honest.

Well, it's only with actual self-awareness that you can hope to have any kind of connection with another person. I couldn't help thinking about how the low res experience actually makes the literary life available to someone who has a day job and caretaking responsibilities. This really isn’t a formed question, but I was thinking about work marked as prestigious in the literary world versus the kind of work that is made and constrained by different conditions of life.

Prestigious, that’s such an interesting word.

I don't know the answer here. I was just thinking about what is the kind of work that is lauded as genius and then what is actually possible in terms of what can be made. What I'm getting at is that I feel like you were able to create a container for yourself in order to continue writing, and still be in this process while you were dealing with what sounds like a lot. It’s not really a question.

I sometimes get those big questions such as what kind of advice would you give to a new poet or artist, and sometimes I think it is to have conviction, because it's so easy to try and mimic the work of people you admire. Or to follow the crowd. If the work calls you to go over there, go. But if the work does not call you to go over there, then maybe you shouldn’t go. I think that kind of conviction to follow your own path wherever it leads you has to be the thing. Be yourself. That's really important. It's incredibly difficult to do in this space that we're in.

I think it's also a feminist thing to do. Because of all of the expectations not only gender-wise, but also culturally.

Yes.

Being a good child.

To be compliant, to be quiet, to be deferential to the systems that oppress us? Maybe at this age, I shouldn't do that anymore.

Yanyi is the author of Dream of the Divided Field (One World 2022) and The Year of Blue Water (Yale 2019), winner of the 2018 Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize. He runs the Asian American Literary Archive.